© Copyright 2011, Ethan Krebs, Justin Levine

James Matthew, Barrie. Nursery Peter Pan. Ed. Olive Jones. Liverpool: Brockhampton Press Ltd, 1961. Print.

James Matthew, Barrie. Nursery Peter Pan. Ed. Olive Jones. Liverpool: Brockhampton Press Ltd, 1961. Print.

Pirates have been prominent in society’s dominant culture for centuries. Pirates are portrayed in countless ways. Some pirates are portrayed as good people stealing from the rich and giving to the poor while others are shown as scoundrels with a lust for murder. In any case, pirates are a dominant grouping of characters in the text Nursery Peter Pan. The original author of the Peter Panbooks was J.M. Barrie. This adaptation of the text was first published in 1961 by author Olive Jones. The text was written for a children’s audience but can also be enjoyed by an older range of people. The text has both colour and black and white illustrations. The colour illustrations were created by Mable Lucie Attwell while the black and white drawings were done by J.S. Goodall. The text and the illustrations flow nicely together to create a balanced book that can be appreciated by all readers. In this exhibit, the category of pirates in Peter Pan will be examined. To start, research has been done to uncover facts about real life pirates in history and compare them to the pirates in Nursery Peter Pan. Pirates in Nursery Peter Pan will also be explained as a whole and how they interact throughout the text. Also, pirates in Peter Pan will be compared to the Hollywood movie Pirates of the Caribbean. The overall critical connection for this exhibit will to determine how accurate pirates in real life history were compared to pirates in Nursery Peter Pan and Pirates of the Caribbean. Similarities and differences will be discussed throughout the exhibit and it will illustrate the facts about the pirates themselves. Ethan Krebs will be discussing pirates in Nursery Peter Pan as a whole, while Justin Levine will be explaining the connection to Pirates of the Caribbean.

The Pirates in Peter Pan

Every story needs an antagonist and there are a perfect set of villains in the text Nursery Peter Pan. The text itself follows the original story of Peter Pan but brings it down to simpler level so that it could be appreciated and read by anyone. In case you haven’t read or heard of Peter Pan, here is a brief description of the text. The book starts off following the lives of Wendy, John and Michael Darling. It seems that their parents are out for the night so in swoops Peter Pan. Peter Pan can be described as the boy who never grew up. Peter Pan, with the help of his fairy friend Tinker Bell, sprinkles fairy dust on the kids which gives them the ability to fly. The kids, along with Peter Pan and Tinker Bell, fly to Never Never Land where they meet the Lost Boys. The Lost Boys are Peter Pan’s crew. Throughout the text, the readers discover that not all is right in Never Never Land. Peter Pan has

a nemesis. This nemesis is named James Hook, otherwise known by his more familiar name, Captain Hook. Hook is seeking revenge on Peter Pan for the loss of his hand. Hook is described in the book to be fearless except for when the crocodile appears. The crocodile is the one who ate Hooks hand in the first place. There are many twists and turns throughout the book. Hook has many attempts at revenge but the overall ending of the book leads to Captain Hook’s demise along with the rest of his pirate crew. The three Darling children eventually make it home and Peter Pan returns to Never Never Land.

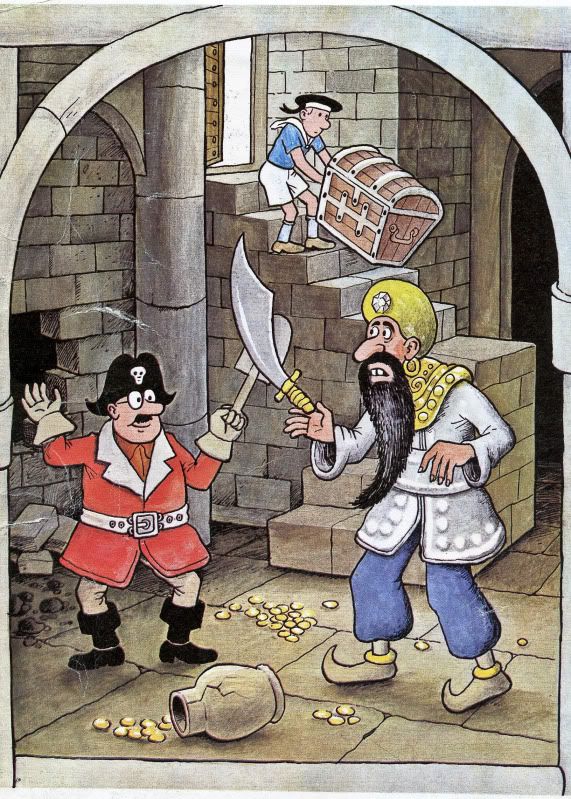

The pirates in the text constantly antagonize all the other characters in the book. As said before, the leader of the pirate crew in Nursery Peter Pan is Captain Hook. Hook can be described as many things in this text. He plays both sides of the spectrum. In some cases, he comes off as goofy, stupid and arrogant. In other cases he has the tendency of being a cold, hard, sociopathic killer. His character description tends to fluctuate throughout the text. There is no real clear objective or answer on why Hook is the way he is. Since the beginning of the text he had his mind set on terrorizing Peter Pan and everyone acquainted with him. The other pirates on the ship do not really have real names and they often change.

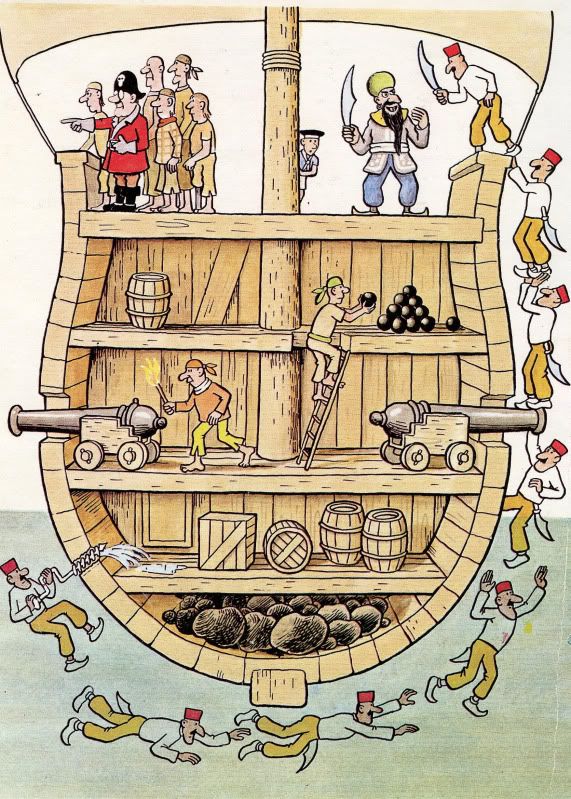

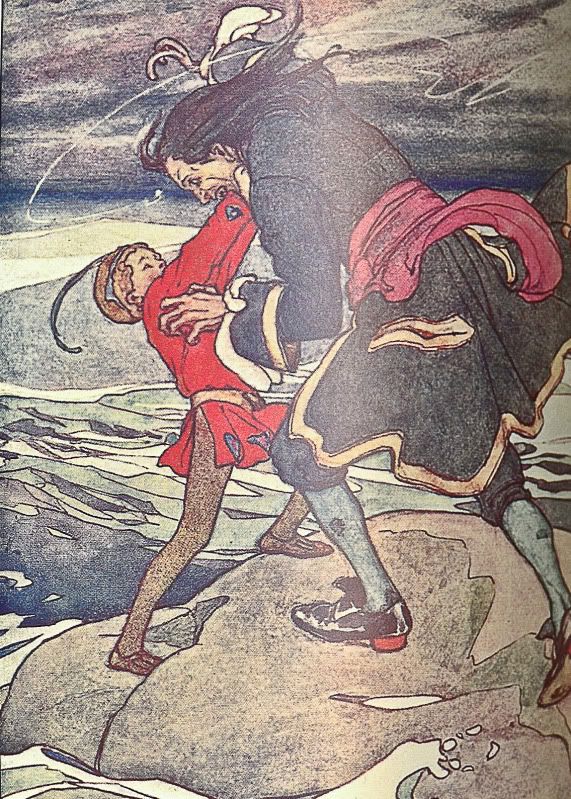

They are often referred to as the crew or mates. The other pirates on the ship are regarded as emotionless, yet loyal. They listen to Hook’s every demand and do what their captain says. They do not really have a personality in the book other than taking orders. The only other pirate in Nursery Peter Pan who is really addressed as a character is Hook’s first mate named Bartholomew Quigley Smeethington, or generally called Smee. Smee is portrayed as a bumbling idiot in the text. If this were a television show, Smee would be the comic relief. Smee often comes up with stupid ideas and Hook is there to correct him. J.S. Goodall did a really good job creating the black and white pictures in the text. The black and white pictures of the pirates really show their evil side, while also showing how goofy and stupid they can be at other times. The overall impression of the pirates in Nursery Peter Pan is that they have a split personality. Hook displays the characteristics of being both goofy and evil. Overall, his evil side comes out more than his other personalities. In the text Hook, along with the other pirates, do countless horrible acts towards Peter Pan and his friends. There are three main things that Hook and the other pirates do in the text which I personally consider beyond evil. The first thing Hook and his crew do is kidnapping Tiger Lily. Tiger Lily is the Indian chief’s daughter. Hook kidnaps her in order to get closer to Peter Pan. This is evil because she is a child. Hook and the pirates are willing to let an innocent girl die just so that they can get a hold of Peter Pan. Of course, Hook’s plan is spoiled but nonetheless he intended to kill both the girl and Peter Pan. The next evil thing Hook and the pirates do is poisoning Peter Pan’s medicine. Tinker Bell learns of this and drinks it herself before Peter Pan can. This almost leads to Tinker Bell’s death, again showing that the pirates will stop at nothing unless Peter Pan is dead. The last evil thing they do is kidnapping the kids and almost making them walk the plank. The main similarities between these three evils is that Hook and the pirates are willing to kill innocent children. They have no gain if they succeed in killing Peter Pan or the others. What do they really accomplish? Even though this is a children’s book, it shows that the pirates are sociopathic killers.

The real question here is: were pirates in real life actually this brutal? J.M. Barrie came up with the character of Captain Hook based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island character, Long John Silver. Barrie did extensive research on pirates before he wrote his Peter Pan books. The truth of the matter is that what Captain Hook did in Nursery Peter Pan wasn’t even half as bad compared to what some other pirates did. Historically, pirates were found to show no mercy. Forget about making you walk the plank, they would simply slit your throat and throw you off the ship. Although brutal and ruthless, the pirates were usually after something. If you had something the pirates wanted, they would simply kill you for it. The pirates in Nursery Peter Pan were dulled down to suit a wider audience. Overall, the facts show that pirates were indeed more brutal than in Nursery Peter Pan and that technically, the characterization of pirates in Nursery Peter Pan is historically accurate.

The Pirates in Pirates of the Caribbean

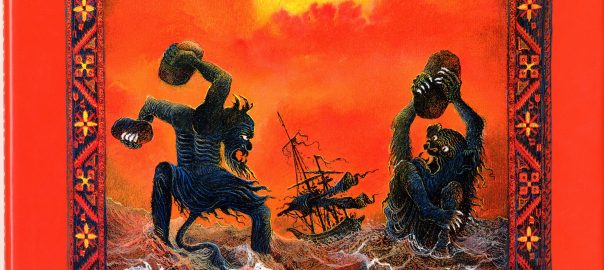

Pirates in Hollywood are portrayed in many different fashions. In general, people were afraid of pirates because pirates were governed by their own pirate code, and they did not follow the law of the land. They were known to be ruthless and violent and would use any means necessary to take whatever they wanted. Most movies base their pirate interpretations on this premise. The pirates in Nursery Peter Pan were no different, although they were tempered for a young audience. The main antagonist in the tale of Peter Pan was Captain James Hook, the lead pirate causing peril and mayhem to Peter Pan and the Lost Boys. It would be fair to say that the evil pirates in Pirates of the Caribbean were based on the same model as Captain Hook and his gang. Both sets of pirates have the same attitude and goals as recounted in historical accounts of typical pirates.

At one point in Pirates of the Caribbean, Captain Barbosa, the captain of the Black Pearl, a haunted pirate ship, is described as ‘a man so evil that hell itself spat him back out’. Captain Hook can be seen in the same way. Barbosa’s kidnapping of Elizabeth, the governor’s daughter of the film, parallels that of Captain Hook’s kidnapping of Tiger Lily. Captain Hook threatens to kill Tiger Lily in order to learn the location of Peter’s hideout.

Barbosa’s men are willing to kill the innocent character Elizabeth in order to lift their curse; however, she is not the only innocent character that the pirates are willing to kill. The pirates in Pirates of the Caribbean were seen invading the town, destroying anything in their way, including defenseless people. The pirates show no mercy, and this is how typical pirates behave in Hollywood films. These are the type of pirates who are the most fearsome. Captain Hook and his gang attempted to murder children by making them walk the plank on their infamous ship named “The Jolly Roger”. These were innocent children.

Barbosa’s men are willing to kill the innocent character Elizabeth in order to lift their curse; however, she is not the only innocent character that the pirates are willing to kill. The pirates in Pirates of the Caribbean were seen invading the town, destroying anything in their way, including defenseless people. The pirates show no mercy, and this is how typical pirates behave in Hollywood films. These are the type of pirates who are the most fearsome. Captain Hook and his gang attempted to murder children by making them walk the plank on their infamous ship named “The Jolly Roger”. These were innocent children.

Pirates in film and fiction, as in real life, are shown to be motivated primarily by greed. In Pirates of the Caribbean, there are two kinds of pirates – the typical ones and the ones who are pirates that are also “good men”. Captain Jack Sparrow, the main character in this film, falls into the latter category. Captain Hook falls into the classification of a typical, evil pirate. Unlike most portrayals of pirates, Captain Jack Sparrow is not portrayed as a “bad guy”. Captain Jack certainly does things to achieve his own ends, but he is not portrayed as violent and uses his cleverness to get what he wants, outsmarting both other pirates and representatives of the British government and making all of them look foolish along the way. Captain Barbosa, on the other hand, more closely fits Hollywood’s typical definition of a pirate and shares many similar characteristics with Captain Hook in Nursery Peter Pan. Hook tries to get revenge on Peter Pan due to the fact that Peter cut off his hand and it was eaten by the crocodile that is always following him, hoping for more of the same. Captain Jack wants revenge on Barbosa, his former first mate, for inciting the mutiny and taking his ship, the Black Pearl. While Hook and Jack are both motivated by revenge in these stories, Jack is willing to help others as long as it doesn’t conflict with his own objectives. Jack’s character does not conform to the typical historical representation of a pirate, which is why the Hollywood scriptwriters created the evil pirates in order to balance out Jack’s uniqueness. The typical historical pirate sailed the seven seas, violently destroying any ship that came within a certain distance, murdering all the innocent people on board with no motive. The aftermath of one such incident is shown at the beginning of Pirates of the Caribbean.

that Peter cut off his hand and it was eaten by the crocodile that is always following him, hoping for more of the same. Captain Jack wants revenge on Barbosa, his former first mate, for inciting the mutiny and taking his ship, the Black Pearl. While Hook and Jack are both motivated by revenge in these stories, Jack is willing to help others as long as it doesn’t conflict with his own objectives. Jack’s character does not conform to the typical historical representation of a pirate, which is why the Hollywood scriptwriters created the evil pirates in order to balance out Jack’s uniqueness. The typical historical pirate sailed the seven seas, violently destroying any ship that came within a certain distance, murdering all the innocent people on board with no motive. The aftermath of one such incident is shown at the beginning of Pirates of the Caribbean.

In the majority of Hollywood movies in which pirates are the antagonists, there are the protagonists trying to bring them down. The audience is usually able to relate to the protagonists and is usually rooting for them to defeat the pirates. That is not the case in Pirates of the Caribbean, where Captain Jack Sparrow is the unlikely hero. In one sense, some may even compare Peter Pan to Captain Jack Sparrow in the sense that both are mischievous and have a child-like quality. They both reject the establishment and live by their own rules. Neither one was clearly good or bad by societal standards. In effect, even

though the Darling children went willingly, Peter pirated them from their parent’s house during the night to achieve his own ends – he wanted Wendy to tell him stories and act as a pseudo-mother to him. The pirates in Nursery Peter Panall abide by the rules of Captain Hook, following him around like his pets obeying his every command, which is a requirement of the pirate code. They are not individually mentioned other than Smee, the pirate that acts as the comic relief of the story. The lack of addressing other pirates generally shows the reader that all the pirates share the same attitude as their leader. They follow in the footsteps of their captain just as the pirates on the Black Pearl all go nameless

and follow in the footsteps of their captain Hollywood’s representation of pirates goes back to some of the first movies ever made that starred buccaneers, such as Treasure Island in 1912 and The Black Pirate in 1926. In both of these movies, a Captain led the crew. The story of Peter Pan came into existence in 1902 where it was found inside a story written by J.M. Barrie called The Little White Bird. The pirates first made their appearance in this story and were then later adapted to Hollywood films in many different variations. In all adaptations of the Peter Pan stories, the pirates always played the roles of the antagonists and Captain Hook always led the pack. The pirates in Nursery Peter Pan and in Pirates of the Caribbean are described in a more comical way and are less sinister and ruthless than reports of actual historical pirates.

Conclusion

In many cases, the depiction of pirates in films is somewhat sanitized when compared to historical pirates in an effort to make them more entertaining and less disturbing to the viewer. This applies even more in films and stories that are geared towards a younger audience, such as Nursery Peter Pan. J.M. Barrie used his extensive research on pirates to create believable images of pirates, even though they are watered-down in Nursery Peter Pan. Overall, our research concludes that in Jones’ adaptation of Nursery Peter Pan, Olive Jones’ portrayal is an accurate representation of the spirit of pirates, while eliminating the gory details.

Bibliography

Barrie, James Matthew. Nursery Peter Pan. Ed. Olive Jones. Liverpool: Brockhampton Press Ltd, 1961. Print.

Beetles, Chris. Mabel Lucie Attwell. London: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1997. Print.

Birkin, Andrew, and Sharon Goode. J.M. Barrie & the Lost Boys: [the Real Story behind Peter Pan]. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print.

Kavey, Allison B., and Lester D. Friedman, eds. Second Start To The Right: Peter Pan in the Popular Imagination. London: Rutgers UP, 2009. Print

Kuhn, Gabriel. Life under the Jolly Roger: Reflections on Golden Age Piracy. Oakland, CA: PM, 2010. Print.

“Pirate Code of Conduct. “ELIZABETHAN ERA. Web. 09 Nov. 2011. <http://www.elizabethan- era.org.uk/pirate-code-conduct.htm>.

Stacy, Jan, and Ryder Syvertsen. The Great Book of Movie Villains: a Guide to the Screen’s Meanies, Tough Guys, and Bullies. Chicago: Contemporary, 1984. Print.

Surrell, J. Pirates of the Caribbean: From the Magic Kingdom to the Movies. San Val Incorporated, 2005. Print