© Copyright 2017 Gillian Dizon, Ryerson University

Introduction

The comics published by Bell Features during World War II are a cultural backbone for what a given society at the time wanted to define as the nationalistic ideology of Canadian identity. Thus, superheroes, their sidekicks and their antagonists came to fruition to address these behaviours or characteristics for all audiences. Generally speaking, if one were to consider these superheroes and their journeys as an example of perfection and goodness, then their antagonists must serve as a way to illustrate to the readers what is considered evil or antithetic to Canadian identity. Tasked with motivating young Canadians during the war effort, the various heroes of Triumph Comics #18 (Ace Barton, Captain Wonder, and Nelvana of the Northern Lights) of Triumph Comics #18 (1944) are often antagonized by villains who are marked by cultural or ethnic stereotypes of Japanese, German and Indigenous people. Understandably, two of these cultural groups derive from the countries the Allies have been warring with during WWII, however, villainizing entire populations of people to young readers would have deleterious effects – especially since many of these ‘villains’ had resided within Canadian borders. This exhibit will analyze the nature of what the writers of Bell Features has decided was necessary to frame Canadian identity and the problems that arise from poor, stereotypical writing.

Comics: Mythology for Kids!

Comic book superheroes are ultimately symbolic. During the golden age of comic books, these characters are meant to embody the ultimate moral good. Understanding the influential power within comic books as something that is akin to mythology would best describe why the portrayal of these characters are so effective and why nations contextually accepted these portrayals – no matter how problematic – at the time of their publishing. As Bart Beaty describes in The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero (2006) that heroes “serve to protect the national interest within superheroic narratives, but they also serve to illuminate national interests in the real world as iconic signs” (428). Beaty further demonstrates that as contemporary mythologies, the actual construction of a hero draws largely from classical mythology (The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero; 2006, 428).

The heroes of Triumph Comics (1944) are no exception to the methods of mythology-based creation. Nelvana of the Northern Lights (Triumph Comics, 1944) created by Adrian Dingle is an example of the “man-god” (The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero; 2006, 428) trope. The first recognizable thing about Nelvana is that she is first discovered by soldiers as a polar bear mounted, otherworldly, magical apparition within an aurora borealis (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 2). Between Nelvana, Ace Barton and Captain Wonder (and briefly, Speed Savage), all three embody the classical heroic attitude Beaty describes as “a dedication to the principles of justice” (The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero; 2006, 428). For Nelvana, her single in this issue of Triumph Comics has allowed her to speak only twice in the comic and yet the only words she tells to the group of men she had just saved from wolves was a vow that she will protect them from the horrors of their enemies (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 9). As for Captain Wonder and Speed Savage in a collaborated issue, the White Mask is described as a “two-fisted, gun packing aid to JUSTICE!” (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 52) while Captain Wonder shames a man for betraying his country for his own profit (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 29). Finally, for Ace Barton’s issue, he is described to be an ace pilot for the R.C.A.F. who tirelessly fights the Japanese despite being outnumbered and stranded (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 38-44). All four of these superheroes serve as an example of classical heroes found in myth who are enhanced beings with an inherently morally good heart.

Antagonists: The Japanese

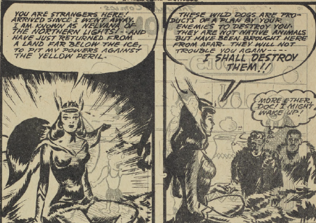

Now to examine what Triumph Comics had understood the Japanese to be at the time of their comics’ conception. As previously stated, the Japanese and the Germans are vilified because they are part of the Axis Powers and have generally become a real life menace for countries that fight for the Allies. On top of crudely drawn features, throughout the entire issue of Triumph Comics #18 (1944) racial slurs such as “Japs” (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 9) and “Yellow Peril” (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 42). But to really drive home the concept of these people as monsters, the artists have depicted these people with less than human features and behaving in an animalistic manner (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 42).

There’s very little difference in the Japanese antagonists in this issue of Ace Barton. The bigger antagonist has slightly more depth as a double agent for the Japanese army but is still drawn in a way that makes him resemble a monster and with no exposition about his character as anything more than a villain. A moment later he commands hordes of Japanese soldiers (pictured above) to chase Ace through the jungle like a pack of dogs (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 40-43).

On a visible and symbolic level, readers of this issue of Ace Barton can sympathise with Ace in comparison to the Japanese not only because he is the hero of this narrative but because he is simply more human in his behaviour. In an article entitled Aboriginality and the Arctic North in Canadian Nationalist Superhero Comics, 1940-2004 (2005), Jason Dittmer and Soren Larsen “Given the visual nature of most superhero media, this reductionism also requires this coherent subjectivity to occupy a specific body, one that is gendered, raced, and super-powered” (53). From a careful observation of this issue, the authors of Ace Barton had intended their young audience to take the Japanese is expendable, traitorous or hostile. Regarding Beaty’s work, he describes that the pantheon of Canadian superheroes “illustrate a set of tensions that surround the intersection of popular culture and federal institutions within Canada” (The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero; 2006, 427). Given the history of Japanese internment camps during this time period, stripping the humanity from the Japanese isn’t a taboo subject for the 1940s.

Germans

In Triumph Comics #18 (1944) Nazis are an often central antagonist appearing in Captain Wonder, Captain Wonder Meets Speed Savage and one-off strips between the larger comic issues. In this publication’s single of Captain Wonder, unlike the Japanese of Ace Barton (Triumph Comics #18, 1944), the Germans are drawn not in animalistic or monstrous ways but rather as menacing people. However, they still exhibit the same behaviour of having no real, in depth motives besides a need to destroy and kill. Since the Germans are a main opponent for the Allies, and therefore Canadians, in WWII, wartime comics are quite active in heavily vilifying the Nazis. In fact they are shown to be an even more fearful antagonist than the Japanese because in the each of the Captain Wonder issues, the Nazis have infiltrated into Canada and successfully killed many civilians (Triumph Comics #18, 1944).

To contrast these Germans against the Canadian superheroes would be presumably an easy task because of how evil they are; but arguably, this places Canadian protagonists into becoming just as unrealistically good. In Beaty’s article he elaborates that when it comes to Canadian comic culture “Canadian superiority [is] rooted in historical circumstance” (The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero; 2006, 434). There is no way of defining moral rightness for the heroes of Triumph Comics #18 (1944) without having to use blatant, one dimensional comparison. Dittmer and Larsen would regard the power in representation because when considering countries as imagined communities, “that power is just as manifest in

the everyday production of national representations as it is in the enforcement capabilities and reifications associated with the organizations dedicated to government” (Aboriginality and the Arctic North in Canadian Nationalist Superhero Comics, 1940-2004, 2005, 54).

Nelvana …and then the rest of the Natives

The most interesting meta-literary comparison between racialized heroes and villains would be how the authors have depicted Indigenous people.

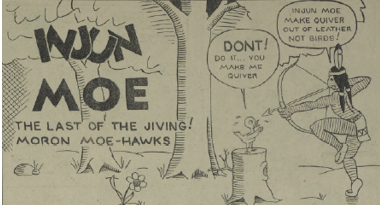

Arguably, the most visual difference between Nelvana and Injun Moe would be how closely Nelvana is drawn to possess Euro-centric features. Injun Moe however, has darker skin for being printed on colourless pages and his hair is tied into braids, adorned in feathers. Since Nelvana is made to fit the heroic, white-centric ideal of Canadian patriotism, she is allowed to be characterized with positive, protagonistic traits associated with her other superhero counterparts as she is seen saving Canadian soldiers from wolves (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 8) and swearing to them that she will protect them from harm (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 9). Injun Moe is racialized ridicule as he is seen taking hyper-literal meanings from other characters such as the bird pictured in the above panel (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 21). The next single within this issue, TANG! (Triumph Comics #18, 1944), also depicts Indigenous antagonists; this time, an entire tribe who ambush a white man and his fellow white sidekick, apparently justified by a cry from a Native chief that “the white men want to disturb [their] peace!” (Triumph Comics #18, 1944, 14). These characters, unsurprisingly, have are draw with ethnic features and traditional dress in comparison to Nelvana. In these three singles, Indigenous people have ranged from heroic, stupid and hostile.

Dittmer and Larsen have addressed this issue regarding Nelvana’s key to heroism as being tied to whiteness and that her ethnic culture isn’t addressed at length (Aboriginality and the Arctic North in Canadian Nationalist Superhero Comics, 1940-2004, 2005). Thus, Nelvana stands as a symbol of the Canadian North more than she is a positive representation of Indigenous people. From another author, Sherrill Grace, Dittmer and Larsen refer to her work to describe this fraudulent sense of cultural representation “that these countervailing ideas are integrated into a powerful discursive formation that ultimately privileges Canada’s southern urban interests over those of northern residents” (Aboriginality and the Arctic North in Canadian Nationalist Superhero Comics, 1940-2004, 2005, 55). Nelvana would have a stronger, more positive impact as a Native character if it weren’t for her imposed whiteness and that every other poor, appropriated depiction of Native (or generally non-white, non-Canadian) people appear in all the major comic narratives of Triumph Comics #18.

Conclusion

What is even more unclear about trying to tie Canadian identity to these heroes is also exhibited in an article by Ivan Kocmarek who writes in Truth, Justice, and the Canadian Way: The War-Time Comics of Bell Features Publications (2016) where Adrian Dingle, the creator of Nelvana of the Northern Lights, that the stories in Triumph-Adventure Comics will “all have a Canadian background” but “ have no indication or assumption of anything “Canadian” in their stories” (150). With that in mind, how can these comic books, which are made to drive the ideology of Canadian identity, be impactful and clear to impressionable, wartime readers? The culture of Canada continued to be undefinable because it is lost within the exaggerated characteristics of their superheroes and supervillains and not honed to any real culture within Canada but is instead framed around defaming other cultures. All in all, this comic book, despite how much it lacks in meaning, serves as a touchstone for the mindset of authors and culture-creators within 1940s and a foundation for better comics to proceed.