© Copyright 2014 Bianca Perry, Ryerson University

Introduction

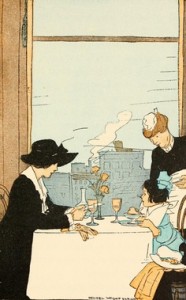

Ruth Fielding in Moving Pictures Or, Helping the Dormitory Fund is a 208-paged juvenile novel situated in Ryerson’s CLA Collection. It was written by W. Bert Foster under the pseudonym Alice B. Emerson and published by the Cupples & Leon Company in New York, 1916. There is one illustration by W. Rogers on the frontispiece of a filming scene in chapter nineteen.

One of Ruth’s main passions in the novel Ruth Fielding in Moving Pictures is, as the title suggests, film. As the book was published in 1916, cinema in the United States was still relatively in its early stages of development. This meant that cinema was a new and popular topic which the American people wanted to know more about. In this way, Ruth’s discovery of film coincides with the country’s discovery of film. Ruth Fielding in Moving Pictures is associated with the Great War. The characters in the novel are not directly involved in or affected by the war since the United States did not join World War 1 until a year after the book was published. However, in association with the war, moving pictures acted as a distraction for people. This worked in several ways, including, but not limited to, the theatre environment, movies for the purpose of entertainment or escapism, and the glamour of movie-making.

Summary

Ruth Fielding in Moving Pictures follows Ruth and her two best friends, twins Tom and Helen Cameron. At the outset of the novel, the trio spots a moving picture company filming a scene. When the main actress falls into the river, Ruth and her friends save the actress and bring her to Ruth’s non-biological Aunt Alvirah to recover at their home, the Red Mill. When Tom shows interest in the actress, Ruth feels a tinge of jealousy, demonstrating the possibility of a romantic future between the two. Even though this is the ninth book in the series, it was not all that difficult to tell what the relationships between the characters were like because the author gives a brief summary of each of the previous books in the third chapter.

Upon meeting the producer, Mr. Hammond, Ruth divulges that she plans to write a moving picture script and Mr. Hammond agrees to read it. An inspired Ruth secretly begins writing her scenario “Curiosity.” Ruth and Helen return to the all girls school, Briarwood Hall, for their final year. Ruth sends her finished scenario off to Mr. Hammond. While at dinner, the West Dormitory, housing all of Ruth’s and Helen’s possessions, burns down. With an expired insurance on the building, there is no money available to rebuild it. The girls each contribute what they can but it is still not enough. Ruth wants to come up with a plan where all the girls can contribute equally since money is not expendable for everyone. When Mr. Hammond replies, impressed with Ruth’s work, he sends her money and tells her he is going to start filming the scenario right away. This is when the two story lines intersect and Ruth comes up with the idea to write a moving picture scenario, aptly titled “The Heart of a Schoolgirl” set at Briarwood Hall, using all the girls as extras. All the profits from the film will go toward helping the dormitory fund. Mr. Hammond approves the idea and Ruth and her team get to work, finding huge success at the end of the novel. Both scenarios written by Ruth are met with enthusiasm by audiences while she gains personal satisfaction from earning money using her brain in something she is passionate about. And finally, Ruth and her friends graduate high school.

Production and Reception

Edward Stratemeyer started a company known as the Stratemeyer Syndicate in which he and hired writers wrote more than 800 books [for children] under 65 pseudonyms (McDowell). While Stratemeyer is a writer, he did not pen the Ruth Fielding series. The Ruth Fielding series was one of the series he produced. In a process detailed in an interview with newspaper Newark Sunday Call (Lawrence), Stratemeyer plotted the novels, gave the outlines to hired writers and edited the manuscript he received from them before sending it to publishers; therefore, playing a huge role in the creation and production of the Ruth Fielding series.

In an advertisement from a New York based magazine, promoting a department store, Ruth Fielding is listed with other girl-specific book series set at low, accessible prices. The fact that this book is listed in an ad for Christmas gift ideas gives a thorough idea of how the book was received and consumed by its audience.

The popularity of the Stratemeyer Syndicate books created much tension. It sparked debate on quality fiction versus literary merit (Soderbergh). Tensions also arose between what early 20th century girls wanted to read versus what their elders, specifically the librarians, thought the girls should be reading. Books with traditional cultural values (i.e. care-taking) and religious behavior were acceptable and promoted by librarians while series books were viewed as immoral and negatively influential (Hamilton-Honey). Despite being discouraged by many adults at the time, the series still soared in popularity and in sales. This speaks volumes about how girls at the time viewed Ruth and how they were interested in, if not inspired by, her path of self-discovery outside of the home.

Working Girls

The Girl Scouts were created in 1912. While there were women trying to keep girls traditional, there was also this entity teaching young girls that they could, if they wanted to, become more than a housewife. The message being promoted here to young girls is different than what they were likely hearing at home, at school, or in society (Revzin). The creation of the girls scouts (which today promotes well-roundedness in girls) around the time of the novel’s publishing date delineates the shift in some attitudes of girlhood.

Around the 1910s, there was also a shift in cultural attitudes toward moving pictures. To keep it relevant, it has been suggested that girl’s books series encouraged young girls to attend movies during that time (Inness). Ruth Fielding decides early on in the book that she wants to become a moving picture writer. Her interest in and pursuit of a career as a moving picture writer would have inevitably influenced many young girls in the world. Ruth unknowingly and unintentionally represented a business not entirely closed to women.

Furthermore, during America’s active war years (1917-1918), women contributed to the war effort. As men were conscripted and went off to war, women were encouraged to “do their bit” and pick up where the men left off, including anything from factory work to farming (Kim). While Ruth Fielding in Moving Pictures was published a year before the war at a time when girls were being scrutinized for participating in work in the public sphere, it is interesting to see how only a year later women were being thrust into all sorts of fields outside of domestic work due to the war.

Overview of Film History

The history of film is long and complex. It includes many facets such as sound, color, lighting, cinematic technique, editing, and longevity. As such, this will be a very brief overview. No one inventor is credited with the creation of cinema. George Eastman, Thomas Edison, and the Lumière Brothers are noted as early contributors. However, many others have contributed to film’s progression. The first motion picture camera was invented in the 1890’s. Within a few years, practical systems for recording and reproducing motion using a single camera came about. Then, short silent films (usually scenes from a stage play or of everyday life) were projected on a screen before a paying (albeit informal) audience. By 1900, filmmakers began using basic editing techniques and film narratives. Around 1910, silent cinema was accompanied by a musical background. Technicolor did not come till much later in the 1930’s (Jacobs). World War 1 marked a transition in the film industry: short one-reel programs transformed into feature films. Theaters became larger and more expensive. Moreover, while war halted the growth of the film industry in other countries, the United States’ late entry into the war allowed the industry to grow exponentially.

Second Row: Upper-class movie palaces.

Theatre Environment

Theatres have always involved a shared space with low lighting where everyone is in attendance for the same purpose: to watch the action occurring on screen. The Nickelodeon (1905) located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was the first theatre in the United States. The creators, Harry Davis and John P. Harris, moved about 100 seats and a projector into an empty store. Attendees were charged five cents (or, a nickel – the origin of its name). The success of this endeavor saw nickelodeon theatres pop up all over the country.

As I began mentioning earlier, a cultural shift occurs in the 1910s. The shift occurs in the idea that moving pictures were only for the working class as they were cheap and unintelligent in content. However, it became seen as something the upper classes could also enjoy as movies became longer and more varied in content and theatres became more luxurious. With advance tickets and reserved seating, these theatres, also known as movie palaces, became sort of replicas of opera houses (Jacobs). They had live orchestras, sloped seating and comfortable chairs. Venues served upward 2,500-6,000 people.

The darkness of the theatre environment suggests a place to hide away for a few hours. Depending on genre, films could move entire audiences to laughter or to tears. Shared experience brought the citizens of the country together in much the same way war propaganda attempted too. Ruth and her friends share the experience of attending the premiere of their film together to watch their work come to fruition. Emotions (nervousness, anxiousness, excitement) run high but are soothed in the darkness.

Movies for Entertainment or Escapism

Regardless of genre, films offered audiences the chance to be figuratively transported to another world, enthralling them with make-believe. While viewing a film, people could escape or be entertained in a few ways. A person could temporarily forget routine, mundane life and live vicariously though the character on screen. The characters on screen would be a part of an exaggerated adventure that everyday people would not or could not take part in. The rise of feature films and the increase in popularity of lengthier films may have suggested that people not only wanted to be entertained for a longer amount of time but that they also enjoyed the escape offered to them in that fixed setting. While Ruth’s second scenario is written in hopes that it will raise money for her school, her first scenario is written purely for the purpose of entertainment.

Glamour of Celebrity

The 1910s saw a rise in interest in the people starring in moving pictures. Certain faces and names became guaranteed to attract audiences (Jacobs). Thus, the glamour of moving-making and those involved in it was born. The creation of this “star system” (where a face equals movie ticket sales) suggests widespread adoration, if not obsession. What follows is the desire to know everything about that person through reading magazines or newspapers, and listening to radio interviews. The idea of a recognizable person, or rather, a celebrity, gave people something else to focus on and something else to speak about. Much like in the novel when Ruth and her friends fish actress Hazel Gray out of a river, not one of them can resist ogling in their own way. Tom thinks she’s beautiful and adores her instantly. Helen wants to be her. Ruth wants to know how she became an actress and question her about the process of becoming a writer.

Conclusion

Ruth Fielding in Moving Pictures follows Ruth as she pursues and achieves her dream of becoming a moving picture writer. This positively influences and encourages other young readers of the series to do the same. As Ruth is discovering cinema in the mid-1910s, so is the rest of the country. At the same time, World War 1 is occurring outside the borders of the United States but remained a constant threat. One of the ways in which Americans distracted themselves from this grim and scary reality was to attend movie screenings. The idea of film as a distraction during the Great War worked in several ways: people could hide away together in dark, semi-intimate rooms, people could become swept away by the stories on screen, or people could become obsessed with the real lives of movie stars.

Link to online version of book

Work Cited:

Emerson, Alice B. Ruth Fielding in Moving Pictures or, Helping the Dormitory Fund. New York: Cupples & Leon Co, 1916. Print.

Gimbels Department Store. Advertisement. The Evening World [New York] 16 Dec 1915: 15. Web. Feb.

Hamilton-Honey, Emily. “Guardians of Morality: Librarians and American Girls’ Series Fiction, 1890-1950.” Library Trends 60.4 (2012): 765–785. Web. Feb

Inness, Sherrie A. “The Feminine En-Gendering of Film Consumption and Film Technology in Popular Girls’ Serial Novels, 1914-1931.” Journal of Popular Culture 29.3 (1995): 169. Web. Feb.

Jacobs, Christopher P. “Development of the Cinema: From Scientific Novelty to a New Art and Entertainment Industry”. Guide to the Silent Years of American Cinema, Ed. Donald McCaffrey. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1999. 1-14. Print.

Kim, Tae H. “Where Women Worked During World War I”. Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Project. Washington State University, 2003. Web. 22 Feb 2014.

Lawrence, Josephine. “The Newarker Whose Name Is Best Known”. Newark Sunday Call [Newark] 9 Dec 1917: n.p. Web. Feb.

McDowell, Edwin. “Syndicator of Bobbsey Twins and Hardy Boys Purchased”. New York Times [New York] 4 Aug 1984. Web. Feb.

Revzin, Rebekah E. “American Girlhood in the Early Twentieth Century: The Ideology of Girl Scout Literature, 1913-1930.” The Library Quarterly 68.3 (1998): 261–275. Web. Feb.

Soderbergh, Peter A. “The Stratemeyer Strain: Educators and the Juvenile Series Book, 1900-1973.” Journal of Popular Culture 7.4 (1974): 864-73. Web. 9 Feb. 2014.

© Copyright 2014 Danielle Parris, Ryerson

© Copyright 2014 Danielle Parris, Ryerson