© 2018 Kelley Doan, Ryerson University

When Canadians think about comic book heroes, most of us refer to characters that are American: they were created in America, they represent American ideas and ideals, and most of the stories are set in American cities or places that, if fictional, are easily recognized as intended to be American. However, while entertainment in Canada does tend to be overwhelmed by American influence, there was a golden age of Canadian comics during which artists and writers took advantage of a pause in access to American content to create Canadian heroes.

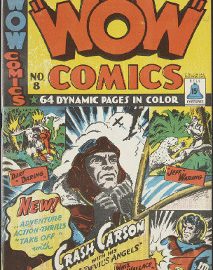

Creator: Bell Features and Publishing Company

Source: http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166671.pdf

In examining Bell Features’ Wow Comics No. 8, I realized that something seemed different about the main characters. These Canadian comic book heroes, in contrast to their American counterparts, were without superhuman powers or superscientific weapons, and this was true of largely all Canadian comic book heroes of the time. For example, in Wow Comics No. 8, heroes Dart Daring, Jeff Waring, Crash Carson, and Whiz Wallace were all simple adventurers (Legault et al.). Most of them were everyman heroes – the average citizen with a passion to set things right and an exceptional dose of courage – with whom readers could identify rather than idolize. Two major contributing factors brought about this new class of comic book hero. Cultural differences in Canada were reflected in their character, particularly a differing notion of what is heroic. More relevant, though, is the impact of propaganda which was used to muster support for the Canadian war effort and was found in all forms of media at this time, including those directed at children. An exploration of the more prominent Canadian comic book heroes as purveyors of the message of unity and call for support sheds some light not only on the origin of future Canadian comic book heroes, but also indicates reasons – beyond a fraught publishing industry – that those later heroes struggled to find more than a niche audience.

Canadian Comics: The Origin Story

Comic books made their debut in the late 1920’s, rising from the popularity of the comic strip. Comic strips were meant solely for entertainment, unlike the already established political cartoon, and the comic book followed suit. There were a number of Canadian comic strips in print, but American artists and publishers had established a foothold in the genre early on, and Canadian comics found little success in syndication beyond our borders (Bell and Viau, “Emergence of the Comic Book, 1929-1940”). Even within Canada, publishers faced financial challenges, in part due to the popularity of the American comic books flooding the market thanks to a much stronger American publishing industry (Edwardson 184).

Creator: Gene Byrnes

Source: http://digitalcomicmuseum.com/index.php?dlid=5640

Copyright: Public Domain

As the popularity of comic strips, known as “the funnies”, increased, the adventure genre strips emerged. Among the first of these was Superman. While he is frequently said to be a Canadian creation – the National Film Board included him in one of their Heritage Minutes and he was part of a collection of stamps commemorating Canadian comic book heroes – the truth is that the connection is very minimal. Superman’s creator, Joe Shuster, was born and lived in Toronto until he was eight years old. He then moved to the United States where he created Superman, who fought for “Truth, justice, and the American way” (Beaty 428). Superman was more than an adventurer, though. He was the first of the superheroes, with powers beyond those of a human being. Children on both sides of the border saw the appeal immediately (Bell and Viau, “Emergence of the Comic Book, 1929-1940”s). Canada’s own Mordecai Richler was a fan, remarking that, “They were invulnerable, all-conquering, whereas we were puny, miserable, and defeated” (Richler 80). Whatever his heritage, Superman’s popularity paved the way for an ever-increasing roster of superheroes, including Batman, Arrow, and Flash Gordon.

Many superheroes got their start in comic strips, and comic books began as compilations of the strips; but publishers rather quickly noticed that comic books had a greater potential, one which included longer-form storytelling and experimenting with elements not possible in strips. Children embraced this new medium as much as they did the superheroes that filled the comic books’ pages, and a new sector of American publishing took off like a speeding bullet. Emphasis is on the American industry, because although there were thousands of fans and a large market in Canada, those Canadians who were part of the comic book boom generally had to move to America to work (Bell and Viau, “Emergence of the Comic Book, 1929-1940”).

As war approached, though, this would change drastically. On the heels of Canada’s declaration of war in 1939 came the War Exchange Conservation Act (WECA), which restricted the importation of non-essential goods including comics. The embargo prompted the formation of Canada’s own publishing industry comprising a group of publishers and their works known later as The Canadian Whites, and provided an opportunity for Canadian artists to produce their own heroes (Bell and Viau, “Canadian Golden Age of Comics, 1941-1946”): heroes which better represented the Canadian audience; heroes who used Canadian cultural references; heroes who could relay messages to the audiences that felt so much more connected to them, a point which did not go unnoticed.

Propaganda in Comics: The Art of Persuasion

The word “propaganda” often conjures ideas of nefarious government deeds, but that is not always or even often the case. It is simply a form of communication with a cause at the heart of its agenda, and can be completely benign or even beneficial. Much like marketing, it is a form of persuasion, but propaganda is enhanced by ideology. As an integral part of a democracy (Batrasheva 8), it is not hard to understand why propaganda is used during war time, when it is of vital importance for governments to unite citizens in support of the war effort.

In 1942, the Wartime Information Board was created from the previous entity, the Bureau of Public Information, changing the mandate from simply providing war-related information to the public to using techniques of persuasion to manage Canadians’ perceptions of and feelings about the war (Young 190-91). Following on the Bureau of Public Information’s failure to rouse support in more traditional and grandiose ways, the Wartime Information Board created the idea of a “people’s war”. Canadians disliked American “brouhaha and victory parades”. They felt that patriotism was being forced upon them, but were inspired by the idea that neighbours together could fight the enemy and build a better society (Young 192-93). It was a young idea that needed a young method of relaying the message.

Among the messages necessary to impart to Canadians during World War II was the integral idea that the war effort, despite the tremendous impact on their lives, was important and good; among the motivations for that message was avoiding the need for conscription and a repeat of the 1917 crisis (English) which divided the nation because French Canada felt disconnected from the cause (“The Conscription Crisis”); in fact the Canadian government eventually avoided the need to send conscripts overseas until nearly the end of the war (Jones and Granatstein). While support had to be stirred in both the men who would go overseas to fight and the women who remained and took on the extra work of supplying the needs of the troops in addition to maintaining their families and communities, it was also important to address the children, whose fathers were suddenly absent and in many cases may never return.

Creator: Pratt and Whitney Aircraft Company Limited

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Our_Answer_All-Out_Production,_Canada,_WWII_Propaganda_Poster.jpg

Copyright: Public Domain

Wartime propaganda is typically of the integration type, seeking to unify society to a common goal (Batrasheva 12). The transference technique, which connects the intended message to something the audience respects or reveres (Batrasheva 16), is especially useful with children as it emulates the parental role. To reach children, the most obvious choice was their current favourite: comic books. Since the favourite characters of the day were already adventure heroes, it was simple enough to send those characters off to war. Combining transference with the plain folks technique – a method aimed at connecting well known figures to activities that should be imitated (Batrasheva 18) – which appealed to both children and those who were on board with the “people’s war” ideal, one of the obvious methods of communication was through entertainment, particularly using popular figures who represented both the war effort’s message and connected with the average citizen. Comic books, with their young market, were an effective medium., particularly since the heroes in Canada’s World War II comics already differed from American heroes in one crucial way: they were not supermen, they were everymen.

Not All Heroes Are Super

The more well-known comic book heroes of the day were American, and the hero among these that best represented American nationalism and support for the war effort was Captain America, who first appeared in 1941. While Captain America began as an average citizen who passionately wanted to go to war and fight the Nazis, he was a sickly man who was not able to enlist. However, he was offered the chance to participate in a government experiment during which he received the Super-Soldier formula and was exposed to “vita-rays”, after which he had a perfect (though still human) body. His physical prowess was enhanced by a shield made of an impenetrable, indestructible, and fictional metal (“Captain America”).

While Captain America is written as a human, the level of perfection raises the character to a level unattainable in reality and carries a super-real shield thus elevating him to the level of superhero. Examining the real-life people that Americans celebrated as war heroes, I found many highly decorated people such as actor Audie Murphy, who at age 19 “manned a machine gun on a burning tank and made a desperate solo attack against German forces”, for which he won the Medal of Honor, and upon which he built his film career (Andrews). This type of hero reflects a preference for a hierarchy of supporting characters following one extraordinary leader, and supports ideals of patriotism and rarefied bravery, and the message that with the support of American citizens the government will send a hero to save the day.

Creator: Leo Baschle

Source: http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166581.pdf

On the other hand, Canada’s main wartime nationalistic comic book hero, Johnny Canuck – who first appeared in 1942, the same year as the Wartime Information Board – was the kind of hero that most Canadians could become. Many knew someone of similar ability, be it their family, friend, or neighbour. Johnny Canuck was an excellent athlete who regularly fought Hitler with his bare hands. Although he had no superhuman powers, weaponry, or armour (Beaty 430) he was designed to be “Canada’s answer to Nazi oppression” (Bachle et al. 1) In fact Leo Bachle was an adolescent when he created Johnny Canuck, drawing him in his own image and including friends and even his teachers in the stories. Johnny Canuck was truly an everyman hero (Plummer).

Creator: Elsie Gregory MacGill

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elsie_macgill.jpg

Copyright: Public Domain

Of course, Canada had some decorated heroes as well, but given our smaller more supporting role, the everyman hero better represented Canadian ideals and mirrored the real-life heroes they venerated, such as Elsie MacGill who led the Hawker Hurricane manufacturing project that supplied fighter planes to Allied Forces and became known as Queen of the Hurricanes, and Leo Major who was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for liberating an entire city by himself, but did so by using his intelligence to trick the Germans rather than brute force (Ferreras).

Conclusion

While Canada and America were united by participation in World War II, their roles were very different. The messages relayed by propaganda to the citizenry were also dissimilar, but this is at least as much due to cultural differences, as Canadians generally saw their mostly supporting role as every bit as important as that of the American troops, not to mention that Canada was involved earlier (Young 190).

While later Canadian hero Captain Canuck – one of the few to emerge in the decades following the war – did have superpowers, he embodied many of the characteristics of Johnny Canuck, and is often confused for a later interpretation of the Canadian Whites hero (Edwardson 189-91). Canadian society had moved on, but Captain Canuck clung mostly to the everyman values that portrayed Canada as “a “peaceable kingdom”” (Edwardson 184), an idea created by the Wartime Information Board to connect to audiences. Later readers had no need for this type of character and, once again inundated with American escapist entertainment, spent their dollars in support of American superheroes.

Nevertheless, the Canadian Whites are an interesting and all too often overlooked part of our literary history. They represent the tenacity of Canadians in the face of war and in the pursuit of entertainment; our ability to band together to fight the enemy in hope of a better world; and our ability to come together and create a whole arts industry that represents Canadians more than it imitates American content, when given the space to do so.

Works Cited

Andrews, Evan. “Audie Murphy’s World War II Heroics, 70 Years Ago.” HISTORY.Com, http://www.history.com/news/audie-murphys-world-war-ii-heroics-70-years-ago. Accessed 10 Jan. 2018.

Bachle, Leo, et al. Johnny Canuck. Chapterhouse Publishing Incorporated, 2016.

Bachle, Leo. Johnny Canuck. 1945.

Batrasheva, Yeldana. Children and the Media: Propaganda Methods Aimed at Children during World War II. 2016, https://www.google.ca/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=12&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjzrqeH2d_WAhWlx4MKHX3iBnkQFghNMAs&url=https%3A%2F%2Felearning.unyp.cz%2Fpluginfile.php%2F58141%2Fmod_data%2Fcontent%2F1862%2FBatrasheva%252C%2520Yeldana_510135_Senior%2520Project%2520Thesis.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0UPYbTLSCTXTppKgA-utKz.

Beaty, Bart. “The Fighting Civil Servant: Making Sense of the Canadian Superhero.” American Review of Canadian Studies, vol. 36, no. 3, Oct. 2006, pp. 427–39.

Bell, John, and Michel Viau. “Canadian Golden Age of Comics, 1941-1946.” Collections Canada, https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/comics/027002-8300-e.html. Accessed 7 Jan. 2018.

Bell, John, and Michel Viau. “Emergence of the Comic Book, 1929-1940.” Collections Canada, https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/comics/027002-8200-e.html. Accessed 6 Jan. 2018.

Byrnes, Gene. Daisybelle Comic on Page 32 of The Funnies. 1 Nov. 1936. http://digitalcomicmuseum.com/index.php?dlid=5640, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Daisybelle_-_The_Funnies,_No._2_02.jpg.

“Captain America.” Marvel Directory, http://www.marveldirectory.com/individuals/c/captainamerica.htm.

Collins, Marjory. New York, N.Y. Children’s Colony, a School for Refugee Children. Oct. 1942. Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:N.Y._Children%27s_Colony_04108v.jpg.

Edwardson, Ryan. “The Many Lives of Captain Canuck: Nationalism, Culture, and the Creation of a Canadian Comic Book Superhero.” Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 184–201.

English, John R. “Wartime Information Board.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/wartime-information-board/. Accessed 6 Jan. 2018.

Ferreras, Jesse. “11 Canadian War Heroes We Can’t Forget On November 11.” HuffPost Canada, 9 Nov. 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2015/11/09/canadian-war-heroes-remembrance-day_n_8475820.html.

Jones, Richard, and J. L. Granatstein. “Conscription.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/conscription/. Accessed 6 Jan. 2018.

Legault, E. T., et al., editors. Wow Comics: No. 8. Bell Features and Publishing Company, 1942.

MacGill, Elsie Gregory. Elsie MacGill during Her CCF Tenure. Apr. 1938. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elsie_macgill.jpg.

Plummer, Kevin. “Historicist: Toronto’s Golden Age of Comic Books.” Torontoist, 20 Nov. 2010, https://torontoist.com/2010/11/historicist_torontos_golden_age_of_comic_books/.

Pratt and Whitney Aircraft Company Limited. Canadian WWII Industrial Propaganda Poster. 1940s. WWII propaganda poster (Immediate source: http://www.pinterest.com/pin/301459768779680901/), Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Our_Answer_All-Out_Production,_Canada,_WWII_Propaganda_Poster.jpg.

Richler, Mordecai. “The Great Comic Book Heroes.” Hunting Tigers Under Glass, McClelland and Stewart, 1968.

“The Conscription Crisis.” CBC Learning, http://www.cbc.ca/history/EPISCONTENTSE1EP12CH2PA3LE.html.

Young, William R. “Mobilizing English Canada for War: The Bureau of Public Information, the Wartime Information Board and a View of the Nation During the Second World War.” The Second World War as a National Experience, HyperWar Foundation, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/UN/Canada/Natl_Exp/NatlExp-14.html.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.