Introduction – By: Alicia Chirrey

Mermaids have been an iconic symbol in folklore ever since their origination in 1000 BC Greece. The representation of this fictitious creature in literature and pop culture has evolved in meaning and appearance. This evolution is based on their early legends and myths of being sexual symbols. Daniel O’Connor’s 1923 version of The Story of Peter Pan, found in the Children’s Literature Archive,utilizes mermaids in a very interesting way. O’Connor uses a combination of mythological representation and symbolic physical features in order to portray their meaning to Never-Never-Never Land. Alice Woodward, a famous British illustrator of books, is best known for her illustrations in The Story of Peter Pan. These works are considered to be very early in her career. In this exhibit, we identify mermaids as illusory creatures that use their sexuality to lure humans into dangerous situations. Alicia Chirrey examines why mermaids are sexualized as temptresses in The Story of Peter Pan and Mamta Patel analyzes the evolution of sexuality in mermaids, demonstrated in featured legends.

The Representation of Mermaids in The Story of Peter Pan – By: Alicia Chirrey

The Meaning of Mermaids to Neverland

The Story of Peter Pan is a narrative about an adventure to a place called Never-Never-Never Land (abbreviated to Never Land in this Exhibit). This is a magical land that represents the unconscious fantasy that lies within the children’s reality. Never Land comforts the crisis of having to eventually accept the responsibilities of adulthood. Time and space do not exist there. The children who live in Never Land are able to live forever in their state of childhood. The transition from childhood into adulthood has key turning points. As Peter Hollindale expresses in A Hundred Years of Peter Pan, one of these important developments that help acknowledge the transformation is the passage into active sexuality (Hollindale 212). Through written description and illustration, Daniel O’Connor and Alice B. Woodward sexualize mermaids as temptresses in The Story of Peter Pan. This portrayal supports the theme of the eternal child by hindering the sexual maturity of the children in Never Land.

About the Illustrator

Alice Woodward is recognized as a well-established, inventive and talented illustrator of books, as Geoffrey Beare describes. Woodward’s illustrations can be found in a variety of books for a vast range of ages. Her work however, has been considered most appropriate for adults, as her usual style has been identified as detailed and macabre. Her work is therefore, very human-like. She is also known for her ability to economically illustrate (Beare 2006). Perhaps these reasons provide explanation for why O’Connor selected Woodward as the illustrator to visually capture the essence of his appropriated story in just 19 images.

Visual and Textual Symbolism

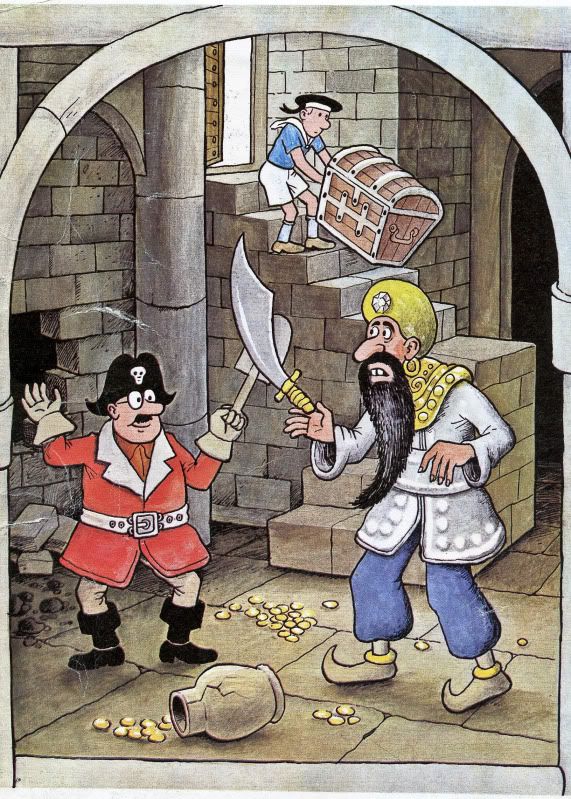

Daniel O’Connor describes the mermaids of Never Land as beautiful, charming, carefree creatures. They spend all day in their Lagoon combing their hair, singing and swimming. From the very beginning, even before the children fly to Never Land, the discussion of mermaids arises. Peter Pan uses the idea of them to tempt Wendy and ultimately, convince her into venturing off to the mystical land.

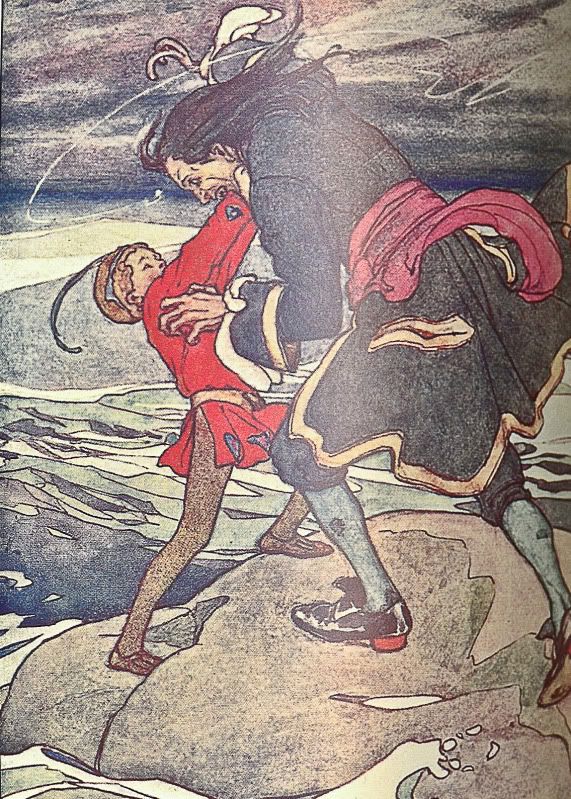

The way Woodward draws the mermaid carefully encompasses sexual allure while maintaining a degree of appropriateness. The Story of Peter Pan only allocates two images in the book to mermaids. The very first image of the mermaid is seen below:

As O’Connor describes, the boys are immediately drawn to the beauty of the mermaid and her charming melody. The mermaid’s long glorious hair is the only thing takes the focus off of her half naked body. This meticulous collectivity contributes to the theme of enticing mystery. The mermaid is a creature the children have never seen before. From the children’s perspective, they can only see the portion of the mermaid the familiar, human half of the mermaid that is above water. The foreign, amphibious portion is mostly immersed in the dark depths of the water.

This unfamiliar creature lures the natural curiosity of the children. The tempting hidden half of the mermaid is what the children lust to see and interact with. The mystery of the unexplored is exemplified by the physical sexuality of the mermaid. The boys even try to catch one as Wendy carefully observes. The action of trying to catch the mermaid for their own objectifies the mermaid, making her less than human. Capturing her would fulfill their sensual desires.

When the mermaid sees the children approaching, she is offended by them and cries out the word: mortals. This outcry of fear and displeasure suggests that mermaids and humans are not allies in this story. In the second picture “She slipped out of his grasp” the children’s hands are only inches away from the mermaid tail as she dives into the water.

O’Connor compares the mermaid’s escape from the boys to be eel-like. This slithery animalistic comparison indicates that the mermaids are like snakes of the sea. The mermaid does not allow the children to fulfill their desires of interacting and acquainting themselves with the mermaid, thus through her escape, keep the children in Never Land.

According to most religions, water represents the unconscious and rebirth (Hallman 67). It holds a great amount of mystery through depth and potentiality, therefore, undiscovered knowledge. In this case, through the use of sexuality, undiscovered knowledge is synonymous with adulthood. In each picture, the mermaid symbolizes the tempting passageway from a world that the children understand to a place that holds mystery of experience. The mermaid is sexualized in order to tempt the children to follow her into the water. Instead, the children hold tightly onto the stable rock. They do not dare follow her for fear of the unknown.

The Historical Context of Mermaids – By: Mamta Patel

Mermaids are mysterious creatures that have been around for many centuries. Most of their myths have derived from Europe. Many of the mermaid’s myths originate from what sailors claim to see. Many Greeks, medieval sailors, and also Christopher Columbus have claimed to have seen mermaids (Ramano et al. 253). Throughout history, mermaids have been portrayed holding a mirror admiring their beauty and combing their hair, this is the exact way they are depicted in The Story of Peter Pan as well. Mermaid’s upper body is made up of a woman and the lower body is fish, however legends describe that they did not always consist of women parts. All legends depict mermaids as singing creatures that lure sailors and then enchant them to death. In historical literature, mermaids are usually portrayed sitting on rocks holding a mirror and combing their long blonde hair. This depiction of mermaids has remained the same in literature; they are also depicted sitting on a rock looking into a mirror in The Story of Peter Pan.

The first legends of mermaids were told by the Greeks in 1000 BC. The first mermaid tale was about a mermaid named Atargatis who was the goddess of love and beauty. She fell in love with a mortal shepherd who she accidentally killed. She was consumed by guilt for losing her loved one that in shame she wanted to punish herself by jumping into the deep waters and turning into a fish. However, her transformation was incomplete because her beauty was so divine. Instead Atargatis formed into a mermaid she was half woman from the upper body and fish from waist below (Adams 56).

The Greeks believed that mermaids were sirens. Sirens are hybrid legendary creatures that had a women’s head, a feathery bird body and large scaly feet. Overtime, the sirens were represented as half woman and half fish. Although the body composition of the sirens changed, they always lured sailors with their charming voices. Sirens used their voices to seduce the sailors, they acted as seductresses and caused the sailors to walk off of their ships and drown. As you can see, sirens and mermaids have many similarities; therefore they are used interchangeably (Ramano et al. 254).

Another legend suggests that the idea of mermaids derived from manatees, which are sea cows. Manatees are linked to folklore with mermaids. Initially mermaids were made of monkey’s body attached to shark tale (Kokai 68). Originally, they were hideous creatures, contrasting how their beautiful and charming features as depicted in literature. It is believed that in 1493, Christopher Columbus misunderstood manatees for mermaids. He announced that mermaids were not half as beautiful as they are painted. This leads us to the myth about mermaids that they are elegant and charming creatures (Ramano et al. 253). Overtime, the physical appearance of the mermaid has changed drastically.

All legends reveal the myth about mermaids being beautiful in cartoons and in fairy tales, along with The Story of Peter Pan. Mermaids are portrayed as beautiful because they are exposed to children through the use of fairy tales. The representations of mermaids are portrayed as role models for young girls, thus, the image of mermaids must be appealing. In reality, all legends about mermaids depict their appearances in various ways, but none are depicted as beautiful. Legends suggest that mermaids originated from “sea cows”, also called manatees. These are giant whale-like creatures. For many centuries, sailors have also mistaken manatees for mermaids. Christopher Columbus, who was the first expeditionary, saw manatees and proclaimed that mermaids are not half as beautiful as they have been painted.

Conclusion – By: Mamta Patel

Daniel O’Connor utilizes the imagery of mermaids by Alice Woodward to represent them as temptresses in Never Land. The mermaids are initially introduced as mysterious creatures that the children of Never Land are curious to know about, however their representations are shown to be alluring for all ages. They are displayed as extremely beautiful, charming, and attractive creatures in The Story of Peter Pan. Focusing on the origin of mermaids, various works have revealed that mermaids have evolved from legendary creatures called ‘sirens’ that had a woman’s head, a feathery bird body, and large scaly feet. Various other sources reveal that mermaids have evolved from whale-like creatures known as “sea cows”, which were generally seen to be unpleasant in appearance. Their appearances had been mistaken, leading to the belief of the existence of mermaids as half-fish and half-woman. This representation of mermaids has led to the portrayal of mermaids as being seductresses who live in the sea. They lure sailors with their enchanting songs and beauty. These creatures have since been used in folklore, such as The Story of Peter Pan, as symbols of temptation in order to create conflict.

Works Cited

Beare, Geoffrey. “Woodward, Alice B.” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature. Ed. Jack Zipes. Oxford University Press, 2006. 14 October 2011. Web

Hallman, Ralph J. “The Archetypes in Peter Pan.” Journal of Analytical Psychology 14.1(1969): 65-73. Academic Search Premier. 13 Oct 2011. Web.

Hollindale, Peter. “A Hundred Years of Peter Pan.” Children’s Literature in Education 36. (2005): 197-215. Academic Search Premier. 16 Oct. 2011. Web.

Adam, Amanda. A Mermaid’s Tale: A Personal Search for Love and Lore. Vancouver [BC]:Greystone Books , 2009. Print.

Kokai, Jennifer . “Weeki Wachee Girls and Buccaneer Boys: The Evolution of Mermaids, Gender, and “Man versus Nature” Tourism.” Theatre history studies 31 (2011): 67- 89,177. ProQuest Research Library. Web. 13 Oct. 2011.

Romano, Stefania , Vincenzo Esposito, Claudio Fonda, Anna Russo, and Roberto Grassi.”Beyond the myth: The mermaid syndrome from Homerus to Andersen’s bicentennial of birth.” European Journal of Radiology 58.2006 (2005): 252-259. Print.