© Copyright 2017 Sahra Alikouzeh, Ryerson University

Introduction

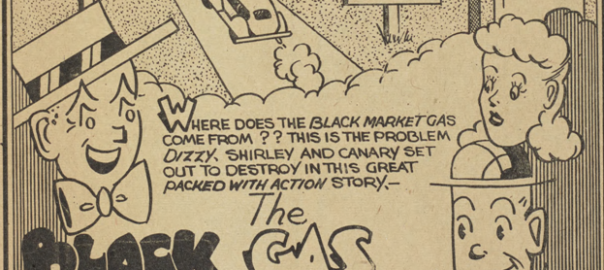

This post will focus on Manny Easson’s eighth comic issue, titled “The Mystery of the Million Dollar Baby”, apart of Bell Features, Great Canadian White Collection. The Great Canadian White Collection is a series of comic books published between the years 1941 to 1946. Due to the importation banning of American comics, this revolutionized an era titled the “Canadian Golden Age of Comics”. (Bell) Issued during World War two, the method of using humor in texts was a popular choice by authors as it not only provided reader’s a mere moment of distraction from the stressful times occurring, but to also allow readers to explore an alternative escapist reality. This post will also discuss the use of the main character, Dizzy Don, who is the protagonist of this comic book intended for children, and some of the influential effects this text has. Understanding how hard the toll of the war was on the Canadians at home, the easygoing nature of the comic book genre can be seen as a stress-reliever suitable for all.

Through the use of humor, authors also took the time to incorporate their own messages within their text to sway the reader’s perspective.

Canadianization

Dating back to the moment in World War 2 where Canada joined the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, Canada provided an indispensable amount of contribution to the generation of British air power. Despite the eventual success due to the tag teaming by both the Canadian air force and the British, Canada made sure to enforce the continued national identification of their personnel. The reason being that national identification allowed for the increase of Canadian political independence. Despite the mixed review received from Britain about the separation, many Canadians embraced the newfound “Canadianization” (Johnston, 2015) Going ahead with this bold move, it was one that was successful as Canadians celebrated, ensuring the importance of their national identity. National identity also increased the amount of Canadians distancing themselves from those whom were seen as non-Canadian. This distance led to the emergence of the anti-immigration perspective.

In order to feel patriotic there is the aspect of appreciating one’s culture and then there is also the put down of other cultures, as a form of whom is to be regarded as superior. The Nazi’s are mocked in this panel due to the faux imitation of their accents. Mocking is a sign of discrediting intelligence and belittling the culture and foreign language being spoken. It provokes this feeling of alienation, humiliation, and disrespect to those of the mocked heritage. This displays how some Canadians felt about German foreigners and their own air of superiority.

Germanophobia

During the time of World War 2 as many soldiers were abroad fighting, Germans in Canada were suspicious of their fellow Canadians. There were many posters and propaganda alike, floating around in promotion of hailing Canadians at war, while at the same degrading the Germans. The method of spreading information through mediums such as texts and the media, allowed the importance of these immigrants’ presence to go unacknowledged and ignored. Instead German immigrant’s importance was replaced with the title of an “enemy alien” (Bassler, 1990) Those with German descent in Canada began to see him or herself as unwanted, to their Canadian neighbors. In comic books there was the mockery of German accents, creation of the German characters as evil and made to look angry, all endorsing these negative stereotypes.

There is a clear binary present as the happy American family is depicted and immediately right after, there is the aggressive German Nazi’s. By illustrating this family as those whom would sacrifice their life in order to save their kin, “The ambassador and his wife huddle around Adorable in an effort to save her life” (Easson, 1943) displays the good North American family image. Something the North American readers would be proud of to relate too. Meanwhile, representing the Germans as those opposing this happy lifestyle, with adjectives such as “merciless” when drawn as attackers.

Humor and Propaganda

Propaganda is the aggressive dissemination of a distinct point of view for a specific purpose. Using persuasive techniques, images, wording and messages to manipulate targeted audiences. By having them assume the propagandist’s perspective is the correct vantage point of view that should be adopted, believed and acted on. (McRann, 2009) Humor allows writers and artists of all kinds to attain a method of expression. Texts embedded within comedic expressions can have large impacts on its audiences, winning over hearts, wars and minds. Humor was used as an approach during the war to construct a national identity, decoding the importance of humor, especially to children during the time of war. Wartime cartoonists were big on getting children involved in the war efforts through their drawings. (Penniston-Bird & Summerfield, 2001) These cartoonists would embrace the gender roles by drawing little boys as soldiers while also promoting the theme of national identity to little girls as well, reminding them to remain patriotic and not make amends with the opposition.

Dizzy Don is introduced as a comedic radio host, who leads the adventures in many of The Funny Comic book issues alongside his pal Canary Byrd. As the main protagonist in this children’s comic book series, his comments and actions are depicted clearly in the story, including his sentiments. Canary Byrd starts off his interaction with Dizzy on the radio saying: “Say Dizzy – when our grocer told you that domestic sardines are 15 cents and imported 25 cents which did you take?” and Dizzy’s response: “Domestic, why should I pay their way over?” (Easson, 1943) Being introduced as a comedian aids the harsh message of how Dizzy feels about foreigners from abroad coming into his homeland. Although the banter can be taken lightly due to Dizzy’s stature as a comedian, the context of the racist message is still present right at the beginning of the story. This also displays clear patriotism, as the support for domestic products over imported is not even something to be questioned by Dizzy.

Conclusion

Humor, especially the sort that is a medium for social and political commentary, plays an important role in the community of a wartime nation. Furthermore, understanding the intention behind a text can be problematic as it reveals discovery on the social impact of the audience. (Penniston-Bird, & Summerfield, 2001) This comic uses the method of humor to promote anti-immigration sentiments, due to the light hearted stance the genre takes, in which the audience is expected to put their guard down. This creates a dimmer focus on the serious aspect of the topic when being discussed, resulting in non-consequential results from its readers. Unknowingly, this targeted audience does not realize the influence Bell Features authors’ texts have on their daily interactions and perspectives, as it creates racist stereotypes and promotes exclusion of those whom are of German descent. This aids explanation as to why there was the continuous racist endorsement; especially as many German Canadians during the war were put under a lot of scrutiny. Putting this in a children’s book allows these ideologies to also exploit the future generation and further these thoughts. Through the use of the main character Dizzy Don and his interactions, he was used as a platform to spread anti-immigration sentiments embedded within humorous texts.

Works Cited

- Twark, E. Jill. “Approaching History as Cultural Memory Through Humor, Satire, Comics, and Graphic Novels.” RULA Archives & Special Collection, Ryerson University. Toronto, Ontario. https://journals-scholarsportal-ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/pdf/09607773/v26i0001/175_ahacmthscagn.xml. Accessed 30 Nov 2017.

- Easson, Manny. The Funny Comic and Dizzy Don No.8: The Mystery of the Million Dollar Baby. Bell Features, 1943. Print.

- Johnston, E. Iain. “The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan and the Shaping of National Identities in the Second World War.” RULA Archives & Special Collection, Ryerson University. https://journals-scholarsportalezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/pdf/03086534/v43i0005/903_tbcatpiitsww.xml. Accessed 30 Nov 2017.

- Bassler, Gerhard P. “Silent or Silenced Co-Founders of Canada? Reflections on the History of German Canadians.” Canadian Ethnic Studies = Etudes Ethniques Au Canada; Calgary. vol. 22, no. 1, Jan.1990, pp. 38–46.

- Penniston-Bird. C. Summerfield. P. “Hey! You’re Dead! The multiple uses of humor in representations of British national defence in the Second World War.” RULA Archives & Special Collection, Ryerson University. https://journals-scholarsportalinfo.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/pdf/00472441/v31i0123/413_ydtmuoditsww.xml. Accessed 30 Nov 2017.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.