© Copyright 2017 Ashlyn Good, Ryerson University

Introduction

Women have been misrepresented for years in comics, especially during the second world war. They were underrepresented within comics because they were not given credit for everything they did do during the war effort, and should be able to at least have a better depiction of themselves within media if they do not get the credit they deserve in real life.

This exhibit will be exploring the portrayal and interpretation of gender roles in comics during World War 2 in Wow Comics No. 9. The story of Whiz Wallace will be analyzed to demonstrate the struggles between power among the gender roles, the language used to describe and differentiate between characters and their roles, as well as the illustrations used which help to depict the discrimination that is implied within the comic.

Language and Interpretation of Character

The language used within this issue of Wow Comics is very discriminatory especially during that time period. It is important because it affects the way we interpret and perceive women in the text. In Whiz Wallace, the language that the author has used implies that Elaine is evidently weaker than Whiz and seems to be dependent on him to save her. This allows the audience to interpret her as the lesser gender which is unfair to women because during that time period in real life they were actually quite useful and sometimes even more useful than men. According to the book, The 10 Cent War: Comic Books, Propaganda, and World War 2, “part of the traditional cultural structure placed men as protectors and women as protected” (Kimble, 39). In Whiz Wallace, Elaine is the more vulnerable character and depends on Whiz to save her most of the time. Elaine is portrayed as this weak woman whom can not seem to defend herself while Whiz is depicted as strong and masculine. This means that gender roles were significant during this time and it is clearly depicted in the story of Whiz Wallace that Elaine was meant to be protected and not the protector because of her gender.

In addition, another character who is also a woman is portrayed as slightly vulnerable even though she plays a powerful role: the Cobra Queen. She is a very powerful female character in this comic but unfortunately even she ends up depicted as vulnerable and more feminine rather than a strong female character. In the comic, the queen is introduced to readers as sad and void (Legault, 60) and as you continue to read on to the next page, the language used to describe the queen begins to change simultaneously. First she was a queen, then she was “queen-like”, then she became a “beautiful princess”(Legault, 61) and later on, she becomes a queen again. The change in description is significant because this means that the author gradually takes power away from this character and by doing so, exerts power onto the opposite gender almost automatically. Since this character was made more vulnerable because of language used to describe her, it proves that during this time period, men were automatically seen as the heroes or the protectors and labourers. Men are the ones who put in the most work according to the train of thought of other men during that time period and the language used within this comic is used deliberately to create an interpretation about a certain character(s).

Illustration and Interpretation of Women

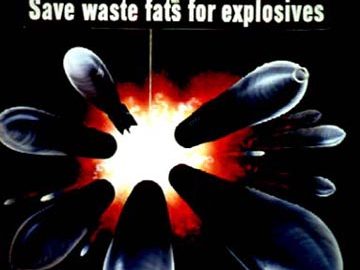

The depiction and illustration of women within this comic is very significant because it adds to how readers interpret their character, especially women. Women are usually highly sexualized within media and it has been this way for a very long time because of the patriarchal society that has impacted it. In Whiz Wallace, the Cobra Queen and Elaine both wear more slim-fitting clothing which exposes more skin creating a more sexualized, alluring appearance which creates a sexualization which brings about the interpretation that women are sexual objects that are portrayed in order to visually please men. During this time period, women were out doing manual labour on the homefront while men were at war. This meant that a change in roles would mean a change in style as well. According to an article written about women during the war, “this change of dress is symbolic of the change in American women’s roles during the war. This adoption of masculine dress, by literally wearing the pants, is an outward expression of the cultural shift in women as homemakers to women as worker”(Hall, 237). Even though women were of great use to the war effort at the time, they were still portrayed as sexual objects with a vulnerable and feminine touch within the comic, especially in Whiz Wallace because even at the end of the comic, the Cobra Queen is clearly attracted to Whiz, even though he is merely an Earthman. Overall, “there are fewer women than men… portrayed as interested in romance or as less-powerful adjuncts to male characters, the women are shown in skimpy clothing and in poses that accentuate their curves while male characters are portrayed as athletic and action-oriented” (Cocca, 7). This demonstrates that women will be seen as lesser than men and the author of the comic has depicted that women are sexual beings which are created in order to please men.

“Mansel in Distress”: Power Struggle Between Genders and Characters

In the comic, there is an interesting power struggle among gender roles within Whiz Wallace, because of the differences and similarities between Elaine and the Cobra Queen, in contrast to Whiz, and his more masculine role. According to the book, Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation, “the superhero genre in comics… underrepresents women in position of power, both as real life creators and as fictional characters” (Cocca, 1). In this comic, the Cobra Queen is a strong female character in the sense that she is the one to save Whiz and Elaine from the army of dwarves that were ready to kill them. The Cobra Queen is introduced as a vulnerable character, who is sad and who seems to have a void as though she is missing something, but then she becomes this powerful character who takes charge and gets rid of the dwarves in order to save Whiz and Elaine. She is an interesting character because she is still portrayed as more vulnerable from Whiz even though she saved his life because near the end of the comic, she seems to be attracted to Whiz and it seems as though there could be a sort of love triangle or even a conflict because there is Elaine who also depends on Whiz for protection and potentially attraction. She calls him a “handsome earthman” (Legault, 63), which means that she must be attracted to him in some way.

In contrast, Elaine is portrayed as more dependent on Whiz to protect her because in the comic she does not seem to be able to take care of things on her own without referring back with Whiz. For example, when the couple was getting attacked the army of dwarves, Elaine was not able to handle it and had to wait for Whiz to save her because her character is depicted as weak and vulnerable and clearly unable to handle herself (Legault, 57). They are referred to as a couple in the comic which means there must be some sort of relationship between them and since Elaine depends on Whiz more, this clearly demonstrates that Whiz is the one with the power between the three characters.

Furthermore, Whiz is depicted as masculine and strong which men usually are within media, especially during that time period, which exerts a type of power which is clearly demonstrated throughout the entire story. Even though Whiz is sort of a ‘mansel in distress’ in this comic, he still contains a significant power of the women in the story. He attracts both female characters with his looks which sexualizes the women within the comic proving them to be more vulnerable than men, making them lose their power almost altogether. The characters in this comic struggle metaphorically with power in relation to who is the more dominant gender.

Conclusion

Overall, women are misrepresented within comics as well as during the war effort at that time. In this comic, even though there was more stronger, female character, she was still depicted as vulnerable with very feminine qualities. Then there was Elaine, who was depicted as the typical damsel in distress, awaiting Whiz to save the day. According to the book Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation, “the underrepresentation of women… and the repetition of inequalities in fiction… are unacceptable and can and must be changed” (Cocca, 5). This means that women should have been given a chance in real life as well as in the media to show how useful they really were as opposed to weak and useless.

Works Cited

- Legault, E. T., et al., editors. Wow Comics: No. 9. Bell Features and Publishing Company, 1942

- Hall, Martha L., et al. “American Women’s Wartime Dress: Sociocultural Ambiguity Regarding Women’s Roles During World War II.” The Journal of American Culture, vol. 38, no. 3, 2015, pp. 232–42. Scholars Portal Journals, doi:10.1111/jacc.12357.

- Bloomsbury.com. “Superwomen.” Bloomsbury Publishing, www.bloomsbury.com/us/superwomen-9781501316579/.

- Goodnow, Trischa, and James J. Kimble, editors. The 10 Cent War: Comic Books, Propaganda, and World War II. University Press of Mississippi, 2016.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.

!["The Black Pirate (1926) Full Movie [BluTay 720p]." YouTube, Feb. 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Z3LAAitmJO.](http://cla.blog.ryerson.ca/files/2017/11/the-black-pirate-229x300.jpg)