Darline Hasrama

500752483

Professor Tschofen

ENG810- 011

Damsel in Distress: Through the Ages

If you have ever seen a movie where a woman is in a problematic situation and she is heroically saved by a man, and you thought “oh, how romantic”, then congratulations because you have been damseled. This trope of “damsel in distress” has been widespread throughout several media mediums and each brings its own variation of it.

Introduction:

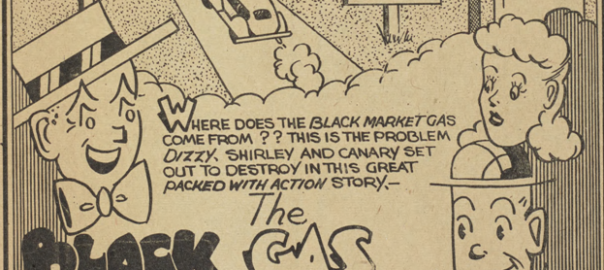

The trope of damsel in distress was most prevalent in Commando Comics issue #20, where it can be observed in a number of stories, particularly in “The Lovely and Unknown Polka.Dot Pirate”. However, being as this comic issue was published in 1943, it is not the first variation of the trope.

The trope of damsel in distress has had been used for many years and but has surprisingly retained many of its redeeming qualities. Through watching the films “The Train Wreckers” and “The Black Pirate”, it can be compared that the identifications of an independent woman, an aggressive, dangerous situation, and the inevitable rescue of the woman by a strong man are notable throughout all mediums.

Importance:

For this research paper I will be comparing the trope of damsel in distress over two silent film mediums, and compare how the trope has either evolved leading up to and including Commando Comics. The objective of this research is to show how a trope that is considered to be very fluent in characteristics throughout all mediums can potentially differ and grow as the years carry on. This topic is an important area of research because there has not been much extensive research comparing the trop through the ages. Most research explains how the trop is normally used to explain a certain message about women and their relationships with men and why these are prevalent is everyday society, however, none of them address their progression.

Mediums:

The first medium is the primary source which is the Commando Comics issue #20. The trope can be identified in “The Lovely and Unknown Polka.Dot Pirate”. The second medium is film. In this case, there are two silent films. The first is “The Train Wreckers” from 1905, this is the earliest film depiction of a damsel in distress. The second is a more popular option called “The Black Pirate” from 1926.

Commando Comics:

The primary evidence that can be found is in the short story titled “The Lovely and Unknown Polka.Dot Pirate” in the Commando Comics issue #20. In this story the Polka Dot Pirate is the intended protagonist heroine who saves the day (and incidentally men). The Polka Dot Pirate figures out how the victim was murdered. Her smart are noted by the villain who says “she’s wise” (Commando Comics p. 25). This quote from the villain points out her intellect in figuring out how the victim was murdered. It seemed that she had won the day but all of a sudden her colleague comes out of nowhere and punches the villain out. He does this right as the villain is about to leave. This shows a power struggle and implies that the woman is incapable of defending herself. Men are presented as a physical dominant force that will overshadow a woman’s intellectual ability to save the day. This ultimately made the female protagonist look like she needed to be saved from a violent situation by a man. It is in opposition to the panels where she is taking charge over the speed boat to catch up to the villain while exhibiting serious physical moves, demonstrating her adventurous side when she is pursuing her target. By having her be a serious heroine who chases after the antagonist, it is a surprise to see that she is eventually overpowered by a man in a physical altercation. The short story also does not end with her having the upper hand, it ends with her male partner having the upper hand giving the readers the illusion that he is the true hero of this story.

Another feature that accompanies the trope of damsel in distress is the appearance of the damsel. Women in comic books are normally given a provocative and overtly sexualized outfit for the pleasurable viewing of males. (Facciani, Lavin) In this particular short story the Polka.Dot Pirate is the only character in the story who is not in regular clothes, instead she is depicted in a superhero costume. She is wearing a cape and a mask, which is traditional of a superhero. Her top portion of the outfit is a low-cut and figure hugging top. There is a deep V cut into her shirt which is a vantage point meant to show off her feminine physique. Her top also seems to be a crop top, bearing the midriff. Her superhero outfit seems to be less about actual functionality and comfort which a crime fighting woman should adorn, and more so about sexuality used to point out the heroine’s clear feminine qualities.

Her outfit is misogynistic to overtly point out that the Polka.Dot Pirate is to be associated with sexuality as opposed to saving the day. Her outfit can be associated with research provided by (Lavin) which shows that women’s outfits were drawn to be more so provocative because it is what men liked to see during the war which explains the Polka.Dot Pirates attire. It can then be thought of as a reflection of the modern world in 1943. Women were receiving more recognition for their intelligence and other skills, however, this cannot be socially accepted in the eyes of a working man. It is then because of the upcoming and modern thoughts of a woman handling more than previously thought was possible, that it had to so forcibly be overshadowed by a man so that men still felt like they asserted dominance over women.

The Train Wreckers:

“The Train Wreckers” is about a woman who falls in love with a train conductor, and so she figures out that his train is going to be overrun by train wreckers and she saves the train. The second time the train wreckers ambush and tie her up to the railroad, and she must then be saved by the men in the train before she is run over.

The chief evidence that surrounds the trope in this silent film is that after she saves her love and the other passengers on the train the first time, she is applauded and it seems like a great moment for women saviors. Nonetheless, she is then ambushed and tied up to the train tracks which visually is the most well known trope of a damsel in distress in film culture. (source) It then follows the general script of her very nearly escaping death before being rescued by his friends and she celebrates profusely that her life is saved.

The contradiction of woman saving men and then almost in retaliation man saving women, shows a power struggle of sorts in regards to what gender can superiorly save the other. It manifests the general ideal that once women can prove they are capable of saving others and being the hero of the day, it is viewed almost as an abomination by men, hence the tying up.

The Black Pirate:

!["The Black Pirate (1926) Full Movie [BluTay 720p]." YouTube, Feb. 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Z3LAAitmJO.](http://cla.blog.ryerson.ca/files/2017/11/the-black-pirate-229x300.jpg)

“The Train Wreckers”, without the traditional clichéd tied to the train tracks bit, “The Black Pirate” demonstrates that even in 1926 women were seen as sexualized objects of affection. Even though the main objective of the movie had no immediate involvement of the princess, her character was a subplot meant to create more content. Because of her sexualized presence in the film and the male go-getter action of the pirate battles, it can be interpreted as a male centric fantasy. (Lavin)

Analysis:

Comparing the two movies that have 21 years between them, the storyline and trope has definitely evolved to be more plot centric and action based but the roles of the female characters have decreased in function. The earliest version sees the female character actually playing an active role in saving the men and being the primary hero which is the most similar to “The Lovely and Unknown Polka.Dot Pirate”. However, the point of the evolution between these 21 years is not only the decreased role of the female but also the transition of the fashion style. The fashion style is an important evolution because it is a depiction of how significant the image of a helpless woman has been advertised. Fast forward 17 years and the comic book is a combination of the main attributes of each film as opposed to an evolution in the right direction.

In the comic, the Polka.Dot Pirate includes a brief element of the woman being the primary savior of the man before she is in turn saved. Since the man was murdered, it is up to her to figure out and apprehend the villain and then for the male companion to save the day. This is the connection between the 1905 medium and the 1943 medium. This shows that the aspect of the female savior is a continued trait that comes back and is popularized due to the power struggle that appears between the men and the women where the man seems to get the last say. In the comic there is also the other element pertaining to how the Polka.Dot Pirate is dressed. (Dunne, Lavin) She is dressed differently than her male counterparts and is seen in short, scantily clad clothes that show off her figure. This is a connection between the comic medium and the 1926 silent film medium. This is a principal similarity between the two because it shows how the way the women are portrayed in the eyes of their male creators. In the 1905 film, the female character is dressed more conservatively to accurately portray the fashion standards of the time. As the fashion standards evolve so does the visual representation of female heroines who are outshined by men. The fashion standards could be reflective of the societal values of time. In 1905 it was very common for women to be wives and homemakers, as opposed to starring in an action films. In the 1920’s it was more socially acceptable, although still promiscuous to see women in a more bodacious outfit such as flapper dresses. As the 1940’s roll in, the ladies focused more on comfortable clothes that allowed them to be traditional caretakers as well as a worker. Even though women had a rougher image due to the circumstances surrounding the era, they were glamourized and sexualized in places where men were able to hold onto the idea of the ideal woman.

Conclusion:

The trope of damsel in distress has certainly evolved from 1905 to 1943, but it was because of those earlier adaptions that the trope was able to manifest itself and become a combination of the two different variations. The comic “The Lovely and Unknown Polka.Dot Pirate” infuses the elements of “The Train Wreckers” by having a female lead be overshadowed by the lesser involved male character and also immerses elements from “The Black Pirate” by having these women dress in scantily clad outfits. This evolution is an indication that the trope is ever changing but inherently incorporates past themes.

Citations

Commando Comics, no. 20, Jan. 1943, pp. 1-36. Canadian Whites Comic Book Collection,

1941-1946. RULA Archives and Special Collections, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada.

Diekman, Amanda B and Emily K. Clark. “Beyond the Damsel in Distress: Gender Differences

and Similarities in Enacting Prosocial Behavior.” The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial

Behavior, 2015, pp.376-386.

Dunne, Maryjane. “The Representation of Women in Comic Books, Post WW11 Through the

Radical 60’s.” PSU Mcnair Scholars Online Journal, Vol.2, no. 1, 2006.

Facciani, Matthew et al. “A Content Analysis of Race, Gender, and Class in American Comic

Books.” Race, Gender & Class, Vol.22, no. 3-4, 2015, pp. 216-226.

Gussow, Mel. “Billie Dove, Damsel in Distress in Silent Films, is Dead at 97: Obituary (obit).”

New York Times, 1998.

Lavin, Michael R. “Women in Comic Books.” Serials Review, Vol.24, no.2, 1998, pp. 93-100.

“The Black Pirate (1926) Full Movie [BluRay 720p].” Youtube, Feb. 2017,

www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Z3LAAitmJO.

“The Train Wreckers (1905) – Edwin S. Porter | Thomas Edison.” Youtube, Nov. 2012,

www.youtube.com/watch?v=xfzjkWD6Z3o.