Children are easily manipulated as they are seen as innocent and naive. Children do not have the education to learn what the real reason is behind the madness that occurs every day. Events will happen all over the world and children will not be capable to grasp a proper understanding as to why it is happening. This is solely due to the lack of education on history. A major historic event that had a change in the world, was World War II in 1939. World War II made an impact on everyone all around the world especially in the media, as it was largely impacted. During this time, comics were very popular and they contained many different stories that were targeted towards war. A comic would show an example of how children were not being properly taught about an event. The use of racism, violence, and hatred was incorporated negatively in these comics. In my comic, there was an advertisement for war stamps that involved the illustration of Adolph Hitler. My comic found on page 15 of WOW Comics issue No. 10 (1945). Specifically focused on the aim for children to purchase war stamps. The purchase of war stamps was easier to persuade to children due to their age and young mentality. The sales of war stamps are one of the factors which helped fund the war, for it was important to keep the children engaged in purchasing. Depending on the perspective, this comic advertisement can be interpreted as a deeper meaning. This can be proven through the history presented, the illustrations, the vocabulary used and the dramatic events which unfolded in front of children in World War II.

Children are easily manipulated as they are seen as innocent and naive. Children do not have the education to learn what the real reason is behind the madness that occurs every day. Events will happen all over the world and children will not be capable to grasp a proper understanding as to why it is happening. This is solely due to the lack of education on history. A major historic event that had a change in the world, was World War II in 1939. World War II made an impact on everyone all around the world especially in the media, as it was largely impacted. During this time, comics were very popular and they contained many different stories that were targeted towards war. A comic would show an example of how children were not being properly taught about an event. The use of racism, violence, and hatred was incorporated negatively in these comics. In my comic, there was an advertisement for war stamps that involved the illustration of Adolph Hitler. My comic found on page 15 of WOW Comics issue No. 10 (1945). Specifically focused on the aim for children to purchase war stamps. The purchase of war stamps was easier to persuade to children due to their age and young mentality. The sales of war stamps are one of the factors which helped fund the war, for it was important to keep the children engaged in purchasing. Depending on the perspective, this comic advertisement can be interpreted as a deeper meaning. This can be proven through the history presented, the illustrations, the vocabulary used and the dramatic events which unfolded in front of children in World War II.

Children and History: Historic Childhood Novelty

I found that the history of World War II was very effective while looking at this comic advertisement. Without looking into the history one would not be able to prove that children were very under-educated and manipulated. The media was able to target children with the use of comics and toys. Children have been targeted for many years, but it was most prominent during World War II because leaders found them to be more vulnerable (Martin Armstrong, 2014). In comparison to adults, children retain more information because they are continuously developing their own personalities and mentalities (David Machin and Theo Van Leeuwen, 2009). Children were targeted in this comic to purchase war stamps, however, they believed that by doing so they were helping fund the war for their nation. The message that they received was positive, as they were helping their families who were within the battle. At an impressionable age and with the passion to be involved, these children tried to come up with any way to make money. With whatever they earned, they would bring it to their school to purchase War Savings Stamps which they pinned into special booklets for post-war redemption. This created an appealing goal for them, by being able to fill and keep track of their unique stamps! Along with the mixed messages, there was the horrible bribery of the children that I found quite appalling. “Children learned to recycle and collect materials, such as metal, rubber, fat, and grease, which were reused to produce useful products for the war. In return for the children’s labour, different incentives were offered to the children such as free passes to the movies” (Veterans Affairs Canada, 2017). Apart from free movie screenings, children enjoyed playing with different toys in their free time. Toys were made to resemble the war; even today I still see these toys exist. These toys can consist of miniature soldiers, plastic machine guns, replica grenades and the full attire (David Machin and Theo Van Leeuwen, 2009). These toys would intrigue children, in relation to the plastic guns, those are not toys, even if they are plastic. These toys would intrigue a child and become an object of enjoyment, as opposed, to teaching them what their real purpose is, which is to injure and kill people. What I immediately thought was how boys-not girls because there was more sexism towards girls if they were caught wanting to play with these war toys; this could resemble their family that was out fighting for their lives. Young boys want to be able to follow in their parent’s footsteps, usually their fathers, which would make these toys more appealing. Further, into the research, it brought me to an article based on a true story made into a comic, about a young girl named Hansi who loved the Swastika symbol (Figure 2).

This is something I found to be extremely inappropriate for a child to love. The Swastika symbol is the official emblem of the Nazi party and a symbol that holds a meaning of hatred. The Hansi comic book was part of a series of biographies of famous Christians in the 1970s. The Christian comic book was based on the autobiography of Maria Anne Hirschmann, who lived through World War II as a victim of the Germans propaganda (Comic Alliance Staff, 2010). She was an avid believer in the Bible, but then found herself intrigued and interested in the swastika.It was concerning as it is found unusual of such difference in an interest into something which negatively impacted the world. Further with age, she then returned back to her Christian faith.It was obvious the moral behind this comic, as it is showing you that your faith will always be there for you even when you do not realize it. By looking back on the history of World War II, I am able to further prove the point that children did not receive the proper education. If they had, these children would not want to resemble the toys they played with to war, misunderstand comics for wanting to help with the war and have a young girl who loved the swastika.

This is something I found to be extremely inappropriate for a child to love. The Swastika symbol is the official emblem of the Nazi party and a symbol that holds a meaning of hatred. The Hansi comic book was part of a series of biographies of famous Christians in the 1970s. The Christian comic book was based on the autobiography of Maria Anne Hirschmann, who lived through World War II as a victim of the Germans propaganda (Comic Alliance Staff, 2010). She was an avid believer in the Bible, but then found herself intrigued and interested in the swastika.It was concerning as it is found unusual of such difference in an interest into something which negatively impacted the world. Further with age, she then returned back to her Christian faith.It was obvious the moral behind this comic, as it is showing you that your faith will always be there for you even when you do not realize it. By looking back on the history of World War II, I am able to further prove the point that children did not receive the proper education. If they had, these children would not want to resemble the toys they played with to war, misunderstand comics for wanting to help with the war and have a young girl who loved the swastika.

Illustration: Visual Stimulation

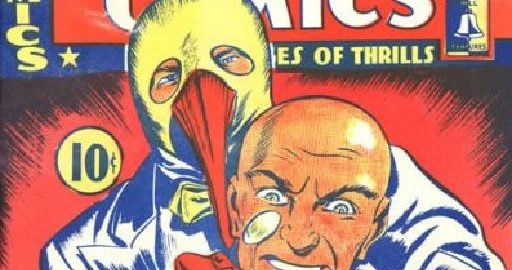

I further my research on my topic by looking into the illustrations displayed in my comic advertisement. This comic I found was unique in the use of illustration, especially when looking at Hitler’s expression while he is saluting. The facial reaction displayed on Adolph Hitler plays a large part in the advertisement (Figure 3).  Looking at his face is unsettling, we are not exactly sure how Hitler is feeling. Hitler looks disappointed when he is giving authority by saluting yet, he is not exactly proud of himself. He also looks guilty. When we see realistic photographs of Hitler, his face is usually flat and he has no emotion shown on his face. However, this comic shows him looking vulnerable and upset. This I find has a major effect on children because it will have the emotional grab; he does not look happy with what he is doing so why would someone else want to follow in his footsteps? It is also seen Hitler holding a swastika in his hand. My findings concluded that the swastika connected with the story of the young girl who loved the swastika symbol. This adds to the fact that children were easily manipulated through illustrations; most likely finding the symbol appealing because they would not understand the meaning behind it. Looking further into the illustration we can take notice of a solider showing force against Hitler. This I found portrayed violence, which should not be portrayed to young children. I think children should see that violence is not something that we approve, yet, this comic is showing our soldiers being violent towards one of the most notorious people in history. It is quite a contradicting illustration when discussing the impact of illustrations affecting children. Although they are young, this is the time their minds start to process information and remember things that they see such as the illustration in this comic. A child finds illustrations more appealing than vocabulary. However, in order for comics to be appealing to the young crowd, the illustrators had to use images rather than vocabulary to catch the individuals eye and have a reminding effect.

Looking at his face is unsettling, we are not exactly sure how Hitler is feeling. Hitler looks disappointed when he is giving authority by saluting yet, he is not exactly proud of himself. He also looks guilty. When we see realistic photographs of Hitler, his face is usually flat and he has no emotion shown on his face. However, this comic shows him looking vulnerable and upset. This I find has a major effect on children because it will have the emotional grab; he does not look happy with what he is doing so why would someone else want to follow in his footsteps? It is also seen Hitler holding a swastika in his hand. My findings concluded that the swastika connected with the story of the young girl who loved the swastika symbol. This adds to the fact that children were easily manipulated through illustrations; most likely finding the symbol appealing because they would not understand the meaning behind it. Looking further into the illustration we can take notice of a solider showing force against Hitler. This I found portrayed violence, which should not be portrayed to young children. I think children should see that violence is not something that we approve, yet, this comic is showing our soldiers being violent towards one of the most notorious people in history. It is quite a contradicting illustration when discussing the impact of illustrations affecting children. Although they are young, this is the time their minds start to process information and remember things that they see such as the illustration in this comic. A child finds illustrations more appealing than vocabulary. However, in order for comics to be appealing to the young crowd, the illustrators had to use images rather than vocabulary to catch the individuals eye and have a reminding effect.

Vocabulary: Cunning Persuasion

Lastly, a strong form of manipulation used throughout this comic is the vocabulary. There are two words that stand out to myself and those words are “heed” and “breed”. Heed is a word that expresses obedience, but also indicates a warning in this comic. Once defining this term and delving deeper into the meaning of it, I realized you have to pay attention to small details in the comic. I looked carefully at this and realized the word heed is used in an intentional way. I needed to focus on the main idea in this comic, which is Hitler. I paid more attention to him after this because what he did throughout his life was not right. His “breed,” aka the Germans, though they were doing good, but when we actually pay attention to the reality of it all, we know that Hitler was trying to create racial purity. In my article, the communicating text starts with: “A jerk called Adolph” which indicates that they are trying to keep an appropriate word for children instead of using a vulgar term (Figure 4).

This portrays to the child that the term “jerk” would be a bad word, but not too bad as to reveal Hitler. In the verse following, “was once a kid” this removes Hitler’s scary nature, allowing children to feel somewhat empathetic. Thus, thinking that he was once like them being weak and vulnerable. Also, without caution to children of Hitler’s true nature, they might desire to be like him one day. Following that in the text, “But, when he grew up just look what he did!” It is implying that the reader would know “what he did” and assumes they would share the same assessment as the comic author. Furthermore, the text says: “Now you” which is speaking directly to the reader of the comic. Also, reverting back to words spoke earlier which were: “can help destroy his breed,” which refers to Hitler’s mission which was to destroy the Jewish people. The ‘you’ in this ad is aimed at its readers to destroy Hitler’s breed. Hitler is known for his wanting to destroy the Jewish. There is a fine line between us attacking Hitler like, he is attacking the Jewish, it is displayed in this ad that we need to destroy his “breed” which does not equal justice. The comic displays Germans as a “breed,” just like animals, they are just something to be killed off as if they do not have to mean. We should not intend to equal the violence, we should show children that we want peace. Lastly, is the quote: “if these words you will but heed… Buy War Stamps!” This is now trying to persuade its reader into thinking that they must buy these war stamps. The vocabulary in this comic advertisement was very particular, they added the persuasion, the double meaning and the second person perspective (WOW Comic, 1949).

This portrays to the child that the term “jerk” would be a bad word, but not too bad as to reveal Hitler. In the verse following, “was once a kid” this removes Hitler’s scary nature, allowing children to feel somewhat empathetic. Thus, thinking that he was once like them being weak and vulnerable. Also, without caution to children of Hitler’s true nature, they might desire to be like him one day. Following that in the text, “But, when he grew up just look what he did!” It is implying that the reader would know “what he did” and assumes they would share the same assessment as the comic author. Furthermore, the text says: “Now you” which is speaking directly to the reader of the comic. Also, reverting back to words spoke earlier which were: “can help destroy his breed,” which refers to Hitler’s mission which was to destroy the Jewish people. The ‘you’ in this ad is aimed at its readers to destroy Hitler’s breed. Hitler is known for his wanting to destroy the Jewish. There is a fine line between us attacking Hitler like, he is attacking the Jewish, it is displayed in this ad that we need to destroy his “breed” which does not equal justice. The comic displays Germans as a “breed,” just like animals, they are just something to be killed off as if they do not have to mean. We should not intend to equal the violence, we should show children that we want peace. Lastly, is the quote: “if these words you will but heed… Buy War Stamps!” This is now trying to persuade its reader into thinking that they must buy these war stamps. The vocabulary in this comic advertisement was very particular, they added the persuasion, the double meaning and the second person perspective (WOW Comic, 1949).

In conclusion, I prove that the media has a large effect on children who lived through World War II. This was shown with the use of the historical information gathered through research of war stamps, as children paid and collected these stamps to help fund the war. The stamps were particularly advertised to children, as they were easy to persuade due to their age and passion for involvement. Secondly, toys which represented different war items allowed a child to have an imagination and feel like their mothers and fathers, who of which did their part to help the war. The true story of Hansi, allows us to understand the meaningful power of the swastika and that person’s faith will always follow them. Moreover, by looking at the illustration displayed in the comic, Hitlers image and expression is evident in showing a negative perspective. As well as, the vocabulary used, which allowed us to see many different aspects being persuasion, double meaning and the perspectives directed. Overall, comics had a lot of impacts, not only on the innocent young boys and girls but also in the aspect of how it portrayed media throughout the event of World War II.

Work Cited

Comic Alliance Staff “Comic Art Propaganda Explored: ‘Hansi The Girl Who Loved the Swastika’.” ComicsAlliance, 17 July 2010, comicsalliance.com/comic-art-propaganda-explored-hansi-the-girl-who-loved-the-swa/

Canada, Veterans Affairs. “Canadian Youth – Growing up in Wartime.” Veterans Affairs Canada, Government of Canada, 24 Mar. 2017, www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/historical-sheets/youth.

David Machin, Theo Van Leeuwen. “Toys as discourse: children’s war toys and the war on terror.” Toys as discourse: Children’s war toys and the war on terror | Critical Discourse Studies Vol. 6, No.1, February 2009, 51-63

Martin Armstrong. “Propaganda & Children – Always the First Target of Leaders.” Propaganda & Children – Always the First Target of Leaders | Armstrong Economics, www.armstrongeconomics.com/uncategorized/propaganda-children-always-the-first-target-of-leaders/.

Stacy Gillis, Emma Short. “Children’s experiences of World War One.” The British Library, The British Library, 20 Jan. 2014, www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/childrens-experiences-of-world-war-one.

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.