© Copyright 2018 Kisha Rendon, Ryerson University

Introduction

Comic books have been regarded through multimedia platforms, scattered on the spectrum of both print and film. When thinking about comics, we envision certain theatrical conventions that were popularized by the D.C. and Marvel American franchises. It would be safe to say that each of us have encountered a superhero movie, or at least an advertisement for one. Coincidentally though, we do not often encounter Canadian comic books in our time the same way people had encountered them during the years of 1941-1946. These years will be remembered as the “Canadian Golden Age of Comics” (“Canadian Golden Age”); when Canadian comics were a revered form of media, and served a greater purpose than providing simple entertainment. During this time, Canadian children turned to comics as an escape from reality, where stories of victory and war time toys would scatter the pages and fulfill their imaginations.

When analyzing an archived copy of Bell Features’ Wow Comic Issue No.12, I found a pattern in the structural scheme of the comic book. This specific issue held a total of six comics/storylines. Three of the said stories were war related with propagational connotations. This especially caught my attention because in comparison, the issue has eleven advertisements/newsletters that are educational/are related to the war effort.

This can be exemplified on the back cover (verso) of the book where there is an advertisement for model airplanes following the comic “Whiz Wallace: Bombers to Victory” created by C.T. Legault (54), which happens to be centered around fighter pilots and aircrafts. Another obvious structural theme was the use of letters or cartoonish lettering over imagery in these advertisements/newsletters, althemore pronouncing the contrast from modern day advertising, which is highly based on imagery and film media. Comic books in this time heavily relied on the use and understanding of literary conventions, thus highlighting the weight at which advertisements/newsletters were used as educational tools.

Although the success of Canadian Comics were a result of the War Exchange Conservation Act (W.E.C.A.) enacted in 1939 (Thomas), through the exploration of the Bell Features Publication Wow Comics Issue No.12, it is reasonable to say that the attempt to refurbish the popular culture of comic books brought forward a medium to propagate Canadian nationalism and the war effort. As well, this research exemplifies that comics hold a larger issue surrounding the ideology of childhood and how children were perceived by the government. Through the exploration and analysis of this specific comic (Issue No.12), I will shed light on the hidden purpose the printing press served in the alternate use of comic books, and will further develop the reasons and educational values expected of children during this time.

Birth of Printing Press: Coming to Comics

Children would read comics as a pastime or form of entertainment. Thus, when the import of American comics was discontinued, the child industry was left open for exploitation. Publishers utilized the prohibition of American comics to establish Canadian comic printing companies such as Bell Features. Founders of Bell Features Publications utilized the publicity of the war time status to establish a Canadian printing press, especially by targeting influential youth who were adamant on supporting different gimmicks in contribution to war effort participation. This resulted in the eruption of the time period called the “Canadian Golden Age of Comics” (1941-1946).

Undercover Propaganda

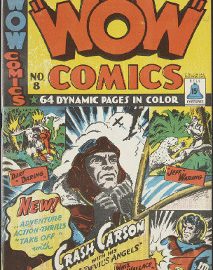

This time brought to light new Canadian heroes, and thus, Canadian based comic book series came to life. To name a few iconic figures; “Crash Carson”, “Nelvana”, “Johnny Canuck”, and etc., were among most of which who followed the mold of an average patriotic citizen, turned sacrificial, brave superhero. Furthermore, Canadian comic books would specifically include true victory stories like that of “Tommy Holmes V.C.” (24) to instill patriotic ideologies in children, and further encourage enlisting in the war and their participation in the war effort. So although on the surface level, comics served as a form of entertainment, publishers would often times include propaganda in forms of advertisement and newsletters, including war toys and self promotion to support, therefore maintaining the war time environment and propagation. Interestingly, during the Golden Age of Comics, education became a crucial aspect in shaping children’s values (Cooke 2), leading back to why true war stories were included in the collection of comics in this issue, and developing the acceptability of “educational” propaganda in children’s entertainment. Through the inclusion of subtle value based advertisements and newsletter additions in between comics and victory stories, comic print cultivated a new level of propagation that changed the meaning of childhood during the war.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, “propaganda” is defined as displays of often one sided idea/opinion based information displayed through images, broadcastings, or publications intentionally spread to influence people’s opinions. Propaganda was commonly seen during both the First and Second World Wars to do exactly this in regard to the upholding of patriarchal values and beliefs. The Cambridge definition of the word “propaganda” insinuates the use of subliminal messaging. In the Wow Comics Issue No.12, there are instances of comics that follow the idea of subliminal messaging. Taking the example of Parker’s Tommy Holmes once again, the comic follows the real life victory encounter of Tommy Holmes being a Canadian soldier, and how he won the Victory Cross. The educational value of this comic, shows to have propagational background in the sense of glorifying enlistment into the front line and educational value through the teaching of a real time event. This is amplified then, by the following overzealous inclusion of advertisements in the children’s print.

Advertisements are typically used to depict messages through mass media. Often times advertising is meant to persuade the purchase of goods or services (Goodis and Pearman), which can be exemplified in this comic issue through the promotion of model plane sets on the back cover (verso). The page is printed in four tone (red, yellow, black, and white) and is displayed with two miniscule drawings of the “Identoplane” box and a boy yelling. All other details on the page are written in different fonts and lettering that mimic/direct the way they are to be read. However, through the comparison of this advertisement against advertisements found in modern day, it is visually more word oriented versus the media we see now. In an article written by Beth Hatt and Stacy Otto in 2011, they discuss the use of visual culture and imagery in advertisements as a way for accessibility to the audience (512). Thus, by using word based advertisements and newsletters in children’s comic books, there needed to be a target audience who could read and understand the content, and were overall meant to be in possession of these comics.

The Canadian Effort: Educating Youth

These findings lead to the question about how children were educated during the war time. The use of comics was an easy solution in educating children through advertisements and newsletters that actually served as politically driven propaganda. Ultimately, the most popular example of educational use in comic books leads back to the highly weighted importance of participating in the war effort. The advertisements for related Bell Features comic books advertise comics aimed toward both boys and girls. In analyzing Issue No.12 further, page 32 stood out as an independent/unique newsletter amongst the others. This newsletter is a stand alone page that has two text boxes with information on the “Torpedo Aircraft”. The page is accompanied by three illustrations of a Nazi German aircraft drawn by the infamous Canadian illustrator, Al Cooper. At first glance the newsletter could be mistook for an advertisement or a one panel comic due to its cartoon-like demeanour, but upon deeper analysis the page is a definite informational newsletter. The newsletter appears to be specifically beneficial to the male audience as it discusses the Torpedo Aircraft in two entire text boxes; which is an example of male gender content. However, during the war time schools as a whole became highly involved in the contributions to the war effort.

Through the outbreak of the war and the installment of the W.E.C.A, school began to revolve around supporting the front line. Educational systems led and focused on contributions to propagational campaigns that would help save the dollar. An example of this would be classrooms being transformed into sewing rooms for girls, where they would “learn” how to sew/knit for the Red Cross organization, and articles would go to servicemen and victims of bombed areas.

www.toronto.ca/archives, 1930, Toronto Guardian, City of Toronto Archives. Copyright is in the Public Domain.

Boys on the other hand were to “learn” how to produce scale models of aircrafts that would go toward training pilots and gunners. Furthermore, this explains why the verso of the comic advertising “Identoplanes” is printed in colour, and makes sense of the use of letters versus images as building aircrafts was associated with school. Education was being strategically interwoven into popular culture through the comic book medium. Moreover, students would often receive education on defence and war emergency training. The type of education included would be how to recognize enemy aircrafts and understanding how they function (Millar “Education”), which is the exact information included on the newsletter from page 32. This thus encompasses the image and value of education as presented to children through political propagation as it was important for students to be educated on certain war time concepts to better protect themselves.

Building Childhood: Concluding Thoughts

The government imposed many political standings over Canadians which is clearly presented through newspapers and printed propaganda, reaching out to parental figures at home, while children were more often concerned with new war toys and other popular culture novelties. School systems held the great responsibility over shaping the values and ideologies of children in a time where there was no structure of understanding or definite knowledge to when the war would end. The war time brought significant changes to the social environment of many families in Canada, which in turn, highlighted school as a facility of direction. Education taught children how to observe and retain knowledge from the world around them, and still plays an important role in shaping personal perspectives. It is important to recognize that children are impressionable and will reflect actions and mistakes. For example, when there is a high standard set on expectations of a noble soldier like Tommy Holmes, children will reflect on that image and mimic it’s value. Therefore, the manipulation of comics as war educated propagational mediums, holds potential power for abuse. Although comics served as entertainment, they were also popular tools used to educate children on serious topics ranging from political ideologies, moral values, and racial categorization. If used/misused with from an ignorant standpoint, there could have been severe consequences in the social development of war time children that would last far into the future.

The most interesting thing about analyzing the issue of childhood education through propaganda in comic books is the lack of thorough research done on this topic. The Golden Age of Comics arose multiple issues that have been overlooked in scholarly work such as: the importance of word oriented/educational advertisements and newsletters in children’s comic books and the purpose that they serve. The values of education in correlation to comic books and popular culture is almost nonexistent. This is concerning considering the weight at which the government influenced Canadian values and ideologies during the Second World War. Continually, there was minimal research regarding how children experienced the war time and war effort movements. Although young and impressionable, the social results of their own experience has not been thought to be analyzed thus far. It was through compiling this research that I found it difficult to produce a connective argument, as this argument does not yet exist, but should exist. It was not hard to point at a page in the comic book and correlate it to a post-war time issue/concern. Wow Comics embraces a great ordeal of information through example illustrations of propaganda and subliminal messaging in story lines. I believe that comic books are detrimental to future studies and analysis on World War II and the experiences of those who lived through it.

In conclusion, through the analysis of the structure of the Wow Comics Issue No.12 and it’s significant use of advertising and newsletters, comic books are proven to have served as educational tools for children during the Second World War. The printing press and pulp print built an opportunity for publishers such as Cyril Bell, to bring forward publication firms such as Bell Features Comics and develop the initial platform for popular culture propaganda. However, it was the importance of education that ultimately motivated the inclusion of subliminal propaganda in comic books. Furthermore, this research envelopes the notion of the child as an important figure in the construction of social values through their impressionable nature, but also the leading figure of direction through their capability to mold the future of Canada. Essentially, the government simultaneously established manipulation and dependence on the education of children through comic books, locking themselves in a feedback loop entailing both the political figures and the children to rely on one another.

Works Cited

Clemenso, Al, et al. Wow Comics, no. 12. Bell Features and Publishing Company Limited, April

1943, pp. 1-65. Bell Features Collection, Library and Archives Canada.

http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166674.pdf

Cook, Tim. “Canadian Children and the Second World War | The Canadian Encyclopedia.” The

Canadian Encyclopedia, 12 Apr. 2016,

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-children-and-wwii.

Cooke, Ian. “Children’s Experiences and Propaganda.” British Library, Creative Commons, 29

January 2014,

https://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/childrens-experiences-and-propaganda.

Cooper, Al. “Torpedo Aircraft.” Wow Comics, no. 12. Bell Features and Publishing Company

Limited, April 1943, p. 32. Bell Features Collection, Library and Archives Canada.

http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166674.pdf

Good, Edmond. “Wow Comics Issue No.12” Wow Comics, no. 12. Bell Features and Publishing

Company Limited, April 1943, cover page (recto). Bell Features Collection, Library and

Archives Canada.

http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166674.pdf

Goodis, Jerry and Brian Pearman. “Advertising.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada,

4 March 2015, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/advertising.

Hatt, Beth, and Stacy Otto. “A Demanding Reality: Print-Media Advertising and Selling

Smartness in a Knowledge Economy.” Educational Studies, vol. 47, no. 6, 2011, pp.

507–26. Scholars Portal Journals, doi:10.1080/00131946.2011.621075.

Legault, C.T.. “Whiz Wallace: Bombers to Victory.” Wow Comics, no. 12. Bell Features and

Publishing Company Limited, April 1943, pp. 54-63. Bell Features Collection, Library

and Archives Canada. http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166674.pdf

Millar, Anne. “Education during the Second World War.” Wartime Canada,

http://wartimecanada.ca/essay/learning/education-during-second-world-war. Accessed 30

September 2018.

Parker. “Tommy Holmes V.C.” Wow Comics, no. 12. Bell Features and

Publishing Company Limited, April 1943, pp. 24-31. Bell Features Collection, Library

and Archives Canada. http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166674.pdf

“PROPAGANDA” Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary.

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/propaganda. Accessed 20 November

2018.

“Save While Supporting the War.” Wartime Canada. 1942. The University of Western Ontario,

London, Ontario. War, Memory and Popular Culture Archives,

http://wartimecanada.ca/document/world-war-ii/victory-loans-and-war-savings/save-whil

Thomas, Michael. “Canadian Comics: From Golden Age to Renaissance (Includes Interview).”

Digital Journal, 18 Aug. 2015,

http://www.digitaljournal.com/a-and-e/arts/canadian-comics-from-golden-age-to-renaissa

nce/article/440981. Accessed 30 September 2018.

“WarMuseum.ca – Democracy at War – Information, Propaganda, Censorship and the

Newspapers.” Canadian War Museum, 14 Nov. 1940,

https://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/newspapers/information_e.shtml.

“Western Technical School – Boys Working on Aviation Motor.” Toronto Guardian. 1942.

Western Technical School, Toronto, Ontario. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1266, Item

19594, https://torontoguardian.com/2016/08/vintage-school-students-photographs/

Images in this online exhibit are either in the public domain or being used under fair dealing for the purpose of research and are provided solely for the purposes of research, private study, or education.