Introduction

The Second World War produced a great number of heroes including soldiers who fought to protect their country, along with mothers and children who supported the soldiers from the home front. At the same time, comics were produced on the home front by new Canadian publishers, eager to provide content to Canadians who no longer had access to those from Canada’s primary trade partner. In his book, Invaders from the North, John Bell describes the comic medium as an “ultimate form of communication” (15), one that was able to convey to young readers during World War II an image of what a hero resembles. These heroes were provided to children to mirror the soldiers who fought for them in WWII. In Wow Comics No. 15, the fictional heroes produced during the golden age of comics demonstrate the patriotic, selfless and courageous traits of the real heroes of WWII, as depicted by Whiz Wallace, Crash Carson, and Dart Daring.

Origins of Canadian Comics

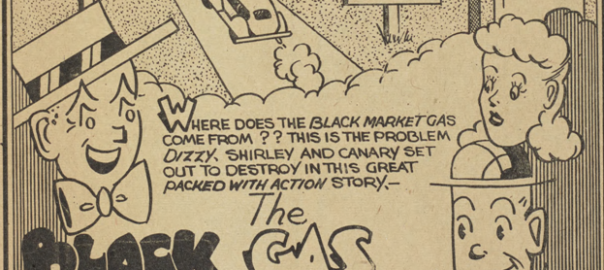

Canadian comic books flourished during the Second World War. After the outbreak of the war, the War Exchange Conservation Act was established in December of 1940 to strength the Canadian dollar and to protect the economy. It restricted all non-essential goods from being imported from the United States, including comic books (Bell, Invaders 43). As a result, an influx of publishers entered the industry, and they began creating Canadian comics without competition from American content. They produced the “Canadian Whites”, which were known for their coloured covered and black and white pages. These comics were produced at an expedited pace in order to fill the gap that was now present in the Canadian industry.

In late 1942, a comic book titled Canadian Heroes was created by Educational Projects of Montreal to provide “more wholesome and edifying fare” for children (Bell, Canuck Comics, 26). It was an informative comic that featured profiles of political leaders in Canada, such as Prime Ministers, governor generals, and RCMP cases. Eventually, publishers “came to realize that Canadian children had developed an appetite for somewhat more thrilling narratives” (Bell Invaders 50). They then began to create additional content of fictional Canadian heroes, which provided children their very own set of heroes to look up to. They paved the way for other publishers to use reality as inspiration for their heroic protagonists during this bleak period in Canadian history.

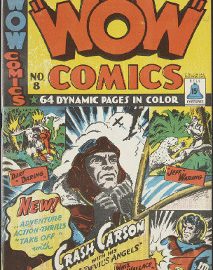

Cy Bell, his brother Gene, and Edmund Legault produced the adventure comic, Wow Comics. During the 1930s, the brothers owned an art firm by the name of Commercial Signs of Canada. After hearing of the ban on comic books, Cy Bell contacted Legault, who had previously shown interest in working on a comic book together, and they began producing Wow (Bell, Invaders 48). The first issue was very successful, selling nearly 50, 000 copies (Bell 25). John Bell observes, “at no time since have English Canadian children grown up with such a wide array of indigenous heroes and superheroes” (Invaders 54). The comics provided a source of heroes for the children, motivating them to support the war effort.

Heroes on The Front Lines

During World War Two, heroes were not only fictional; the war was a catalyst that produced selfless individuals, who were patriotic towards their country and courageous in fighting for a safer nation. Of the Canadian servicemen who fought, very few had experience in the military prior to the war (Engen 25). Many individuals who came to serve in the war became known as “citizen soldiers,” as they were amateur combatants who usually had volunteered for the war effort (Engen 34). They were seen as superior to those who were conscripted as a belief was held that “citizens should provide their own defence” (Engen 34). Citizens were encouraged to join the war effort on their own account, without being required to do so.

Individuals who volunteered for the war were much more revered than those who were conscripted. The soldiers who served overseas, were almost all volunteers; Canada had the second largest all volunteer field force, after Britain, during the war (Engen 33). For most of the war, those who were conscripted remained on the home front, ready to fight for the defence of the country. The National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) was issued in 1940 in order to provide defence for Canada. The soldiers “mobilized” under this act were not required to serve overseas, at least not for the majority of the war (Engen 33). It was thought that only soldiers who had volunteered of their own free will should serve overseas.

Many soldiers who did sign up to serve were the children of veterans of World War One. These soldiers were influenced to volunteer because of their family connections to war and the pressure to serve (Engen 30). In Strangers in Arms, Robert Engen describes a soldier named Charles “Chuck” Daniel Lloyd, whose father had served and died in the First World War, and whose older brother had been a peacetime militiaman (Engen 37). Although the soldier’s reasons for joining the war were not recorded, Engen theorizes that his family connections with war were a cause for him joining the war effort. Lloyd joined his brother in the Hastings & Prince Edward Regiment of the militia and together they enlisted upon the declaration of war in 1939 (Engen 37). Lloyd, who died in 1943, was an example of an individual who was motivated by past generations, and who no doubt influenced the next generation of soldiers.

Among the real-life heroes of the war, was an individual who saved a small Dutch town, called Wilnis, from harmful destruction. On May 4, 1943, Warrant Officer Robert Moulton set off with almost 600 bombers for a raid on Dortmund Germany (Wattie 2). Upon turning home, his plane was attacked by a German bomber and began to burn (Wattie 2). As it descended, he instructed his four crew members to eject, though only two of them were able to parachute to safety (Wattie 2). Witnesses reported that Warrant Officer Moulton’s bomber was directed at their village, but suddenly banked away from it (Wattie 2). Moulton demonstrated selflessness as he sacrificed his life for the lives of the civilians in the town. According to one captain, “this still has a great impression on the citizens; In their mind, Moulton was a hero” (2). Volunteers like Lloyd and Moulton demonstrate the attributes that Wow Comics sought to illustrate to children through the fictional heroes they created. In demonstrating these characteristics, the comics were preparing the soldiers of the next by presenting them with the heroes and roles models they needed to look up to. They sought to raise the next generation of soldiers, modelled on the fictional characters of the comic.

Heroes on Paper

In Wow Comics no. 15, the heroic protagonists demonstrate selflessness, patriotism and courage in an effort to teach children the exemplary qualities they should exhibit. In “Whiz Wallace and The Desert Demon,” Whiz Wallace and Elaine are travelling through the desert, trying to reach ‘El Frasher. When Elaine expresses her concerns for their lengthy journey, Whiz Wallace reassures her by saying “Courage, Elaine!” and offers her a cooling drink to refresh her. They are confronted by a group of wild horsemen who plan on stealing their horses, and Elaine. Whiz selflessly attacks some of the men, even though he is outnumbered and unarmed. He attacks them, using only his fists, while the desert men have large knives and guns. Though he fights heroically, he is eventually overpowered.

Whiz Wallace is tied up by the desert men, while Elaine is restrained. As Elaine is pleading for their lives, a unit of German bombers fly overhead and notice the desert men, “Himmel! Two white people is being tortured by desert savages!” (Legault 17). They decide to rescue the two from the desert men, and then take them as prisoners of war. Even when facing more danger, Whiz remains heroic and brave. The Nazis who capture them declare that their Fuehrer has a plan of invasion, and will strike soon. Whiz counters “All I have to say is, your Fuehrer better not be too sure of himself!” (Legault 19). Whiz is portrayed as confident in his country’s ability to defeat the Nazis, even though he is being detained by them. He exhibits heroic qualities that illustrate to children to be courageous and selfless in order to protect others, and support their country.

In “Crash Carson and His Devil’s Angels,” Crash Carson is fearless and courageous as he takes on Nazis and German bombers. Carson and two other soldiers attack a group of Nazis to prevent them from getting away. Carson’s sidekick, Tank, throws a grenade, and the three of them charge the Nazis. Later, Crash and the other soldiers encounter another group of Nazis who are armed with a machine gun. One of the soldiers drives straight for the Nazis as Crash and Tank fire at them.

Bell Features Collection, Library and Archives Canada. http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166677.pdf

At the height of the story, a Nazi escapes and tries to steal one of their allied planes. Crash Carson runs after him immediately to prevent the Nazi from escaping and harming others. He puts himself at risk in order to save the lives of those the German may hurt. By running to stop the German from taking their bomber, Crash Carson is teaching children to be courageous in supporting the fight against the Nazis, and to be patriotic in fighting for their country. Crash Carson, after defeating the Nazi, takes control of the bomber as he and another soldier come under fire. They defeat the German bomber, but then are mistaken by their ally to be an enemy bomber, but Crash Carson saves them again using his piloting skills. This illustrates Crash Carson’s ability to think and act under pressure while they are being attacked by the enemy. As a hero, he demonstrates courage in the face of danger as he puts himself in harms way to avoid potentially harmful situations from becoming onto others.

Bell Features Collection, Library and Archives Canada. http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166677.pdf

Dart Daring in “Dart Daring and The Castle in The Sea” exhibits courage and selflessness as he tries to rescue Loraine after hearing her scream. Dart Daring is thrown into the water after their ship hits a castle in the middle of the sea. After being tossed overboard, Dart is shown sinking into the sea, with one panel only showing his hand above the water. His companions, Loraine, the captain and Frank, enter the mysterious castle after a drawbridge is let down for them. They mistakenly believe that whoever lowered the bridge, would help them find “the brave sir Daring.” His companions are then trapped inside the castle, and suddenly Dart resurfaces from the water. Though his own life is in danger, Dart is concerned about Loraine when he hears her scream from beyond the now closed drawbridge, within the castle. Upon hearing her scream, Dart courageously scales the wall, with shaking fingers, in order to selflessly rescue the damsel in distress. After almost drowning in the sea, Dart emerges ready to save Loraine from the “great danger” she may be in.

Conclusion

During the Second World War, heroes existed in real life and on paper. The fictional heroes of Wow Comics no. 15 were created to illustrate the heroic features that soldiers demonstrated during the war, in order to raise children and adolescents to exhibit those qualities. The soldiers of the front lines, and the protagonists of the comics displayed selflessness, patriotism, and courage in the face of their opponents. Whiz Wallace, Crash Carson and Dart Daring exemplify the same qualities of WWII soldiers, and provided role models for children. They helped to raise individuals who cared about and protected others, were brave in all situations, and who were loyal and supportive of their country. The heroes of the frontlines and those on paper helped to create future heroes.

Works Cited

Bell, John. Canuck Comics. Matrix Books, 1986.

Bell, John. Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe. The Dundurn Group, 2006.

Engen, Robert. Strangers in Arms: Combat motivation in the Canadian Army, 1943-1945. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.

Legault, E. T. “Dart Daring: The Castle in the Sea.” Wow Comics, no. 15, 1943, pp.47-55. Bell Features Collection, Library and Archives Canada. http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166677.pdf

Legault, E. T. “Whiz Wallace and The Desert Demons.” Wow Comics, no. 15, 1943, pp. 12-20. Bell Features Collection, Library and Archives Canada. http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166677.pdf

Tremblay, Jack. “Crash Carson and His ‘Devil’s Angels.’” Wow Comics, no. 15, 1943, pp. 26-35. Bell Features Collection, Library and Archives Canada. http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166677.pdf

Wattie, Chris. “Last of Doomed Bomber Excavated: World War II Mission: Canadian Pilot Praised as Hero for Steering Plane Away from Dutch Town.” National Post, September 2002. http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/330182777?accountid=13631.

This is something I found to be extremely inappropriate for a child to love. The Swastika symbol is the official emblem of the Nazi party and a symbol that holds a meaning of hatred. The Hansi comic book was part of a series of biographies of famous Christians in the 1970s. The Christian comic book was based on the autobiography of Maria Anne Hirschmann, who lived through World War II as a victim of the Germans propaganda (Comic Alliance Staff, 2010). She was an avid believer in the Bible, but then found herself intrigued and interested in the swastika.It was concerning as it is found unusual of such difference in an interest into something which negatively impacted the world. Further with age, she then returned back to her Christian faith.It was obvious the moral behind this comic, as it is showing you that your faith will always be there for you even when you do not realize it. By looking back on the history of World War II, I am able to further prove the point that children did not receive the proper education. If they had, these children would not want to resemble the toys they played with to war, misunderstand comics for wanting to help with the war and have a young girl who loved the swastika.

This is something I found to be extremely inappropriate for a child to love. The Swastika symbol is the official emblem of the Nazi party and a symbol that holds a meaning of hatred. The Hansi comic book was part of a series of biographies of famous Christians in the 1970s. The Christian comic book was based on the autobiography of Maria Anne Hirschmann, who lived through World War II as a victim of the Germans propaganda (Comic Alliance Staff, 2010). She was an avid believer in the Bible, but then found herself intrigued and interested in the swastika.It was concerning as it is found unusual of such difference in an interest into something which negatively impacted the world. Further with age, she then returned back to her Christian faith.It was obvious the moral behind this comic, as it is showing you that your faith will always be there for you even when you do not realize it. By looking back on the history of World War II, I am able to further prove the point that children did not receive the proper education. If they had, these children would not want to resemble the toys they played with to war, misunderstand comics for wanting to help with the war and have a young girl who loved the swastika.

This portrays to the child that the term “jerk” would be a bad word, but not too bad as to reveal Hitler. In the verse following, “was once a kid” this removes Hitler’s scary nature, allowing children to feel somewhat empathetic. Thus, thinking that he was once like them being weak and vulnerable. Also, without caution to children of Hitler’s true nature, they might desire to be like him one day. Following that in the text, “But, when he grew up just look what he did!” It is implying that the reader would know “what he did” and assumes they would share the same assessment as the comic author. Furthermore, the text says: “Now you” which is speaking directly to the reader of the comic. Also, reverting back to words spoke earlier which were: “can help destroy his breed,” which refers to Hitler’s mission which was to destroy the Jewish people. The ‘you’ in this ad is aimed at its readers to destroy Hitler’s breed. Hitler is known for his wanting to destroy the Jewish. There is a fine line between us attacking Hitler like, he is attacking the Jewish, it is displayed in this ad that we need to destroy his “breed” which does not equal justice. The comic displays Germans as a “breed,” just like animals, they are just something to be killed off as if they do not have to mean. We should not intend to equal the violence, we should show children that we want peace. Lastly, is the quote: “if these words you will but heed… Buy War Stamps!” This is now trying to persuade its reader into thinking that they must buy these war stamps. The vocabulary in this comic advertisement was very particular, they added the persuasion, the double meaning and the second person perspective (WOW Comic, 1949).

This portrays to the child that the term “jerk” would be a bad word, but not too bad as to reveal Hitler. In the verse following, “was once a kid” this removes Hitler’s scary nature, allowing children to feel somewhat empathetic. Thus, thinking that he was once like them being weak and vulnerable. Also, without caution to children of Hitler’s true nature, they might desire to be like him one day. Following that in the text, “But, when he grew up just look what he did!” It is implying that the reader would know “what he did” and assumes they would share the same assessment as the comic author. Furthermore, the text says: “Now you” which is speaking directly to the reader of the comic. Also, reverting back to words spoke earlier which were: “can help destroy his breed,” which refers to Hitler’s mission which was to destroy the Jewish people. The ‘you’ in this ad is aimed at its readers to destroy Hitler’s breed. Hitler is known for his wanting to destroy the Jewish. There is a fine line between us attacking Hitler like, he is attacking the Jewish, it is displayed in this ad that we need to destroy his “breed” which does not equal justice. The comic displays Germans as a “breed,” just like animals, they are just something to be killed off as if they do not have to mean. We should not intend to equal the violence, we should show children that we want peace. Lastly, is the quote: “if these words you will but heed… Buy War Stamps!” This is now trying to persuade its reader into thinking that they must buy these war stamps. The vocabulary in this comic advertisement was very particular, they added the persuasion, the double meaning and the second person perspective (WOW Comic, 1949).