INTRODUCTION

Native Americans are now known for being spiritual, environmental, and nomads and unfortunately, colonizers have used stereotypes to create an alternate assumed identity with this knowledge. Previous to now the stereotypes of the Native identity was wrong, but as time has progressed it has slowly corrected itself. Thanks to the education high school now offers on the basics of native heritage and history stereotypical aspects have faded slightly and the presumed slights have become less prominent. This is a step in the right direction to reconciliation for the atrocities Indigenous North American communities have faced, from residential schools to cultural assimilation to the numerous issues surrounding reserves and broken treaties.

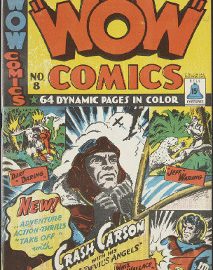

The “right step forward” to reconciliation mentality in North American society has not always prevalent in history. Throughout the 1800 and the 1900s, First Nations fought and defended Canada in both World Wars but were not given the right to vote. Indigenous people were consistently depicted as the enemy in mass consumed media even in medias geared towards children. In the collection of comics called the “Canadian Whites,” it was common to find this villainous depiction. Even more so it was common to see the reliability these comics had on racist, propagandistic stereotypes of the Indigenous community. In order to understand this racism, analyzing how Canada has treated Native Americans in the past will explain how these people and society interacted. Researching into the specific comic “WOW, no. 10” (published in January of 1942) and the origins of the racism found in this specific comic created numerous questions.

community. In order to understand this racism, analyzing how Canada has treated Native Americans in the past will explain how these people and society interacted. Researching into the specific comic “WOW, no. 10” (published in January of 1942) and the origins of the racism found in this specific comic created numerous questions.

Why is the native populace depicted in mass consumed media negatively and in a severely racist way without the care for separate tribal identities? Even with Native Americans aiding the war effort greatly through enlistment the government refused to acknowledge the help until much later. Instead, deciding to show off propagandistic comics that portrayed “true” Canadians to be solely white Canadians who are superior and used this belief to fuel what the government of past and present 1940s wanted for Canada’s imagined future. Examining the Native influence on Canada prior, during, and after the war, the understanding of how this racism and altered depiction of Natives will become more clear and highlight that the imagined identity was a predominantly white, European, Christian population. All those who were not these characteristics, be it those who were First Nations or otherwise, were to be expunged or assimilated.

THE IMAGE OF THE “RED SKINNED SAVAGE”

In the short story found in WOW no. 10 called “The Iroquois are Back,” by Kathleen Williams, the time period revolves around the mid 1600s. The features three young men; Henri, Jaques, and Louis, all who venture out of the community against previous discretion due to “red devils,” the Iroquois being seen in the surrounding area. First Nations people have survived on this land for thousands of years, promoting spirituality and prosperity. As colonization became the dominant identity to cultivate the land for its resources, Native Americans became closed off on reserves, far off from society all while colonizers lived on the ground that the tribes once claimed. The use of ‘red devil’ is used as a depictor of the red undertone skin (a racist stereotype of First Nations people) and disassociates any good inherent reason for the Iroquois to be in the area or attack. It makes Indigenous people the enemy before they had really caused any issues, an enemy who is weaker and less formidable than other white people.

Colonization created a bias against Natives and that is shown when Henri, Jaques, and Lo uis single-handedly kill Natives for over two hours, a feat that is then congratulated when they are rescued by others from their community. They slaughtered many Native Americans to represent that they are protecting themselves from the “red deviled savage.” The murder of people was celebrated because they were the antagonist of the story for existing in an area that was once theirs solely. They were villainous for existing as Indigenous tribes and people were viewed as “primitive, strange and alien” (Sangster. 191-200) and were shamed for acting like “the behavior of the Eskimo.”(Sangster. 1991 200) The actions and values of the First Nations were shamed as the “cultural hierarchy that cast white, Euro-Canadian modernity as preferable and superior” (Sangster. 191-200) was always considered better.

uis single-handedly kill Natives for over two hours, a feat that is then congratulated when they are rescued by others from their community. They slaughtered many Native Americans to represent that they are protecting themselves from the “red deviled savage.” The murder of people was celebrated because they were the antagonist of the story for existing in an area that was once theirs solely. They were villainous for existing as Indigenous tribes and people were viewed as “primitive, strange and alien” (Sangster. 191-200) and were shamed for acting like “the behavior of the Eskimo.”(Sangster. 1991 200) The actions and values of the First Nations were shamed as the “cultural hierarchy that cast white, Euro-Canadian modernity as preferable and superior” (Sangster. 191-200) was always considered better.

This “savagery” is seen again in the story “Jeff Waring” by Murray Karn when the Native chief and his soldiers arrive on a Native war canoe and automatically it’s assumed that the natives torture and kill them. It then progresses to Jeff Waring, and his friends being tied to be burnt at the stake and are only saved when the chief’s son is cured by the “white man’s” medicine. Savagery is assumed in the comic just as common nature for the Indigenous creating only negative, primitive depictions of the supposed tribe. The need to immediately resort to burning them on the fire as an act of savagery and then only transitioning from an evil portrayal when the white man’s medicine is used to help save the chief’s son paints all tribes as primitive. It all relies on the dependence for progress that the colonizer can bring to the Indigenous community.

CREATING MIXED CULTURES

The war changed many aspects of society, altering acceptance and economic prosperity. The decriminalization of Japanese Canadians who were put into internment camps and Italian immigrants were no longer viewed as “enemy alien” after 1947.

Enemy aliens “referred to people from countries, or with roots in countries, that were at war with Canada…. during the Second World War, people with Japanese, German and Italian ancestry.” (Patricia Roy, Canadian Encyclopedia) This was not something that transferred to Native Americans, who by this point still were not given the right to vote federally (July 1, 1960 legislation passed to federally vote) and were viewed in disregard as during the war. This lack of acceptance was shown best in the depiction of two separate tribes; the Iroquois and a tribe from the Amazon. They have no relation to one another in any way be it physical, environmental, time period, nor are in the same story of the comic book yet look identical to each other in both the “Jeff Waring” and “The Iroquois Are Back.” These outfits are identical in the comics, both using similar furs and feathers.

Traditionally the Iroquois used “furs obtained from the woodland animals, hides of elk and deer.” (Kanatiyosh. 1999) whereas Amazonian tribes wear woven plant-based clothing or body paint. This was common especially during the time period of “Jeff Waring” as the cloth used by westerners was harder to make and obtain. This is due to the temperature difference and the cultural significance of clothing. Traditionally in the Amazon the fewer clothes one would wear the higher the rank in the tribe similar to the more body paint worn the higher the rank as well. Whereas clothing in the Iroquois tribe is beaded, has bells, and sewn on designs to show rank as the weather in Canada is much more frigid, especially in the 1600s when the comic “the Iroquois are back” takes place.

This link of identicality is seen in the way the faces are constructed in the illustrations. Both drawings have shown Natives with high cheekbones, dark eyes, large foreheads. These identities, that are very different, look identical for the purpose to show that all Natives are the same in appearance, culture and savagery. This represents ideas of assimilation into colonization as the Native community was not even worth an actual identity and instead is just clumped together as one. This ideology of missing individuality was the “ultimate goal of eliminating the “Indian” as an entity apart from the mainstream of Canadian society.” (Sheffield. 17) The lack of identity also shows that they are less superior to those who have actual defining features and differences, specifically that they are less important, in both the comic and real life than the white westerners.

This link of identicality is seen in the way the faces are constructed in the illustrations. Both drawings have shown Natives with high cheekbones, dark eyes, large foreheads. These identities, that are very different, look identical for the purpose to show that all Natives are the same in appearance, culture and savagery. This represents ideas of assimilation into colonization as the Native community was not even worth an actual identity and instead is just clumped together as one. This ideology of missing individuality was the “ultimate goal of eliminating the “Indian” as an entity apart from the mainstream of Canadian society.” (Sheffield. 17) The lack of identity also shows that they are less superior to those who have actual defining features and differences, specifically that they are less important, in both the comic and real life than the white westerners.

THE MOCCASINS ON THE GROUND.

In the comic book as a whole, there is not a single mention of positive actions that the Native Americans had done. During “The Iroquois are Back” it depicts violence as if that is all the Natives are capable of with statements such as “the Indians closed in for the kill, hatchets raised, tomahawks waving.” (Williams. 29) War heroes are the pride of a nation and meant to hold their heads up with glory. They receive medals, are put on the local news at six, and written about in the paper. All acts of heroism during these wars are assumed to have already been discussed except there is never any mention of the aid the Indigenous tribes provided to the war effort.

Violence is promoted in the comic as second nature to the Natives but highlights nothing of the violence that some Natives were told to do while enlisted. It promotes a figurative “one-sided” coin alluding to this being only true depiction with accuracy as to how Indigenous tribes act. This ideology is further emphasized during “Jeff Waring” where the first interaction with the Indigenous tribe in the Amazon was a war canoe approaching the heroes boat. Instantly, the Natives are a threat once again. This portrayal has created conflict as there was, during its publication, Natives fighting for Canada in Europe. With no mention as to Indigenous men and women in the military, it has “resulted in narratives that are selective, partial, biased and distorted” (Harvey et al. 257) Natives were known in the armed forces for “voluntary enlistment and conscription of thousands of First Nations men.” (Sheffield. 43) The Society of American Indians, a group that helped the fight for Native rights to citizenship, even went as far as to put in their Journal that “Already we hear the tread of feet that once wore moccasins; already the red men are enlisting.” (Sabol. 268) Yet the history books have erased their participation as until later in the search for the Canadian identity was it acceptable to be native. The narrative stayed consistently negative until the tropes and stereotypes that are found in the comics became less politically correct closer to the beginning of the 2000s and were filtered out.

RECONCILIATION

Reconciling on past governmental and societal mistakes is an everyday goal in Canada as the acknowledgment of Native cultural genocide becomes more well known across the country. In doing this, images and tales such as those found in “the Iroquois are Back” and “Jeff Waring” become slowly more obsolete. There have been recent steps backward such as Johnny Depp in the movie “The Lone Ranger” but as the populace began to understand the sacrifices that Native Americans have suffered at the hands of colonization and it has become a topic more serious and more informed. Reconciliation started in Canada and the United States when the US granted citizenship to Native Americans as “Congress passed the law to reward Indians for their service and commitment to the country at a time of great need.” (Steven. 268) Unfortunately, all efforts were put on pause during the 1930s as it was the Great Depression. Tensions were rising in Europe which forced reconciliation to be pushed back until the 1960s, when voting in Canada federally was granted to all Native Americans. After that historical event that came into effect July 1, 1960, reconciliation has tardily progressed into slow positive change.

IN CONCLUSION

In the creation of Canada, Native American people have been treated as second-class citizens and have been the public enemy for an extended amount of time. From the fight to conserve their traditions and values to the consistent work towards continued reconciliation. As society progressed to be more inclusive, once again Natives were left in the dust and forced to continue the fight for equality. The images, text and subliminal messages in the comic book WOW comics no. 10 are present due to consistent colonial influence and racist stereotypes that emerged from that time period, continuing even to this day. The results of reconciliation have slowly chipped away at these stereotypes but these remarks still leave a lasting mark on the Native community in Canada.

WORKS CITED

Sheffield, R. Scott. The Red Man’s on the Warpath. UBC Press, 2004. pp 43 https://books-scholarsportal-info.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/en/read?id=/ebooks/ebooks0/gibson_crkn/2009-12-01/3/404358 Accessed 10 Oct. 2018.

Karn, Murray. “Jeff Waring.” Wow Comics, no.10. pp 15-25, http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166673.pdf. accessed 10 Oct. 2018.

Williams, Kathleen. “The Iroquois are Back.” Wow Comics, no.10. pp 27-29, http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166673.pdf. accessed 10 Oct. 2018.

Sabol, Steven. “In search of citizenship: the society of American Indians and the First World War.” Oregon Historical Quarterly, 22 June 2017, p. 268+. Academic OneFile, http://link.galegroup.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/apps/doc/A499696071/AONE?u=rpu_main&sid=AONE&xid=0c276e89. Accessed 10 Oct. 2018.

Raynald, Harvey L., et al. “Conflicts, Battlefields, Indigenous Peoples and Tourism: Addressing Dissonant Heritage in Warfare Tourism in Australia and North America in the Twenty-First Century.” International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, vol. 7, no. 3, 2013, pp. 257-271. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/1412780619?accountid=13631. Accessed October 16/2018.

Sangster, Joan. “The Beaver as Ideology: Constructing Images of Inuit and Native Life in Post-World War II Canada.” Anthropologica, vol. 49, no. 2, 2007, pp. 191-209. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/214174078?accountid=13631. Accessed October 16, 2018.

Sheffield, R. Scott. “Veterans’ Benefits and Indigenous Veterans of the Second World War in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States.” Wicazo Sa Review, vol. 32 no. 1, 2017, pp. 63-79. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/674309 Accessed October 16, 2018.

Kanatiyosh. “Iroquois Regalia.” Haudenosaunee Children’s Page. 1999. http://tuscaroras.com/graydeer/pages/childrenspage.htm Accessed November 20, 2018.

WORKS CITED: PHOTOS

ALL PHOTOS FALL UNDER FAIR USE POLICY. RYERSON UNIVERSITY IS NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY DAMAGES CAUSED.

Brazilian Natives in Traditional Clothing. *Royalty free* Released free of copyrights under creative commons CC0. https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1254856 Accessed November 12, 2018.

Fair use expired copyright- “The Iroquois are Back.” Wow Comics, no.10. pp 29, http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.chttp://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166673.pdfa/e/e447/e011166673.pdf. accessed 10 Oct. 2018.

Fair use expired copyright- Goody, Edmond. WOW Comics, no.10 Front Cover page. January. 1942. http://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/e/e447/e011166673.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2018.